On April 12, 1865 the Civil War ended when Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his command to U.S. General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia. The port city of Mobile, Alabama had come through the war unscathed. However, half the city was destroyed in a major tragedy over a month later when twenty tons of captured Confederate gunpowder exploded in a warehouse that was being used as an arsenal. The entire northern part of the city was laid in ruins by the explosion.

Mobile surrendered peacefully

When Union troops entered the city of Mobile unopposed on April 12, 1865, Mobile surrendered peacefully thereby avoiding the destruction that other southern cities had experienced during the war.

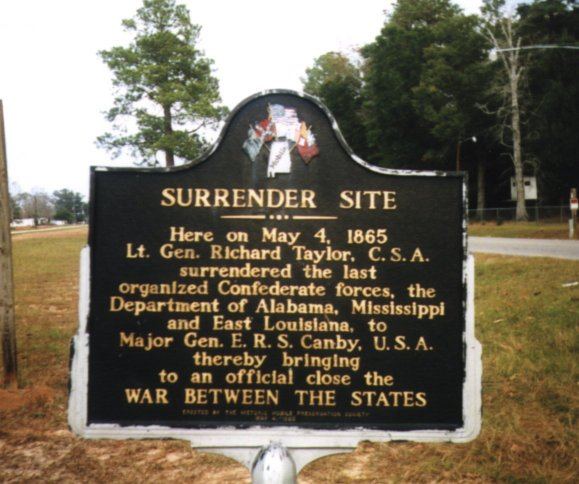

Confederate General Richard Taylor met U.S. General E.R.S. Canby April 29th at the Magee Farm in Kusla, Alabama to discuss the terms of surrender for the armies of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana, the last contingent of the Confederate Army east of the Mississippi.

Beneath a large oak tree near Citronelle, Alabama, later named the Surrender Tree, the last of the Confederate troops east of the Mississippi laid down their weapons on May 4th. Martial law was immediately declared by the Union Army in Mobile.

Union Army occupies Mobile, Alabama

The occupying army established an ordinance depot at the corner of Commerce and Lipscomb Streets. The depot is said to have contained about 200 tons of explosive ammunition and gunpowder. A little more than a month later, smoke was seen rising from the depot on May 25th and moments later, the ammunition exploded.

It was reported, “so terrific was the explosion that it destroyed or damaged all buildings in the area bounded on the north by Bloodgood Street, on the west by Conception Street, on the south by St. Anthony Street and on the east by the river. Windows in the Battle House, which suffered an estimated $15,000 damage, and in buildings as far south as Conti Street, were shattered. Force of the blast was so great that it caused carriages to capsize on Royal Street, and horses to collapse as if shot to death. A man was blown off the wharf into the river at the foot of Church Street, and a steamer and schooner were wrecked at their moorings in the river.”1

The explosion was tremendous

“A reporter for the Mobile Morning News who rushed to the scene of destruction described the explosion as “a writhing giant gaunt and grim” poised in midair. . . bursting shells, flying timbers, bales of cotton, horses, men, women and children co-mingled and mangled into one immense mass. The heart stood still, and the stoutest cheek paled as this rain of death fell from the sky and crash after crash foretold a more fearful fate yet impending; the lurid flames began to leap farther from the wreckage. Old and young, soldier and citizen vied with each other in deeds of daring to rescue the crumbled and imprisoned.”2

It was estimated that 300 people were killed by the explosion and the falling debris. The Nashville, Tennessee Morning News reported, “As soon as the explosion was hear, Major General Granger and Colonel Shipley repaired to the scene of destruction, where they remained, giving directions and seeing them carried out.

The General dispatched a messenger to Brigadier General Dennis, ordering him to detail all the soldiers in the city and vicinity, and to impress all the men found in the streets to aid in rescuing the wounded and staying the progress of the fire, and in twenty minutes an efficient body of men was on the ground….”

The flaming debris that had been thrown, fell onto buildings and started fires in the northern half of the city and before the fire died, the entire northern half of Mobile was consumed.

The Dead

The Nashville Morning News and Janesville Weekly Gazette gives some names of Union dead and wounded. “We saw the bodies of Mr. McMahon, who was in charge of the carpenter work, of Capt Foord acting quartermaster, and the purser of the steamboat Laura“ which vessel was lying on the marine ways opposite the city – who was killed while sitting at his desk, by either a piece of one of the numerous shells, which filled the air in that neighborhood, or by a fragment of brick. Mr. McMahon was on one of the steamers near the Planter’s Press, on duty when killed. A sailor was killed by the explosion of a shell while working on the engine of one of the fire companies…

A number of the bodies received are so burned and mutilated that recognition is impossible. Some of them are so blackened that it was with difficulty their friends and relatives could identify them, even when not disfigured by mutilation.

The shrieks of the poor wives, daughters, and mothers, as a body would be borne out of the ruins, were heart-rending – each expecting to find some loved one’s mangled and blackened corpse. Several fainted, and were borne away on the stout arms of the tender-hearted soldiers present…..

Steamer almost torn to pieces

The steamer Col. Cowles, Captain Tucker, was lying opposite Planter’s Press, and was almost torn to pieces by the shock, and soon after took fire and was completely consumed. The mate tried to move her before she took fire, but failed. Captain Tucker was badly injured, and two negroes – a cabin boy and firemen- missing, supposed to be lost.

The Kate Dale was entirely destroyed. Only two of the crew were found missing. Officers all safe.

A schooner loaded for New York, having some passengers on board, among them a gentleman named Baker, formerly connected with this office, was destroyed. No word has been received as to the fate of the passengers and crew.

Among the wounded are the following: Michael Sefton, C, 46th Iowa; Ben Hauker, E, 52d Indiana; W. L. Hall, K, 7th Illinois; Jacob Gorett, R, 29th do [ditto – K, 7th Illinois]; J. M. Thorp, F, 29th Illinois; Nathan Reynolds, A, 23d Michigan; H. Isham, A, 23d Missouri; C. B. Morgan, B, 33d Illinois; J. J. Tiddan, D, 93d Indiana; Henry Doser, G, 29th Wisconsin Infantry; Corporal J. W. Lynch, A, 23d Wisconsin; Private S. D. Rogers, D, 20th Iowa Infantry; Privates Philander Grisas, battery C, 3d Illinois; Gabriel Keimeche, A, 23d Wisconsin; Privates August Hurley, A, 23d Wisconsin; C. Williams, a, 23d Wisconsin; Alex. Heacock, d, 24th Indiana; W. Balshka, A, 19th Winconsin; Geo. Abbott, A, Missouris light artillery; Daniel C. Heely, B, 29th Illinois; Henry S. Bacon, James A. Wells, John Casebeer, 1, 23d Wisconsin; Benjamin Brewer, Co. C, 69th Indiana; Hosea H. Young, Co. G, 37th Illinois; Joseph Chapman, Co. H, 29th Wisconsin; Corporals Wm. J. Wilson, Co. C, 29th Illinois; Edmund Blunt, Co. F, 29th Illinois.

Among the wounded men of the Quartermaster’s department are Joseph McQueen, Lawrence county, Ind.; W. F. Van Wry, Indiana.

The cause of the explosion was never determined but many northern newspapers blamed it on vengeful Confederate soldiers. However, after being investigated, the generally consensus was that it was an accident. Property loss was put at $5,000,000 and the number of casualties was never determined, although it has been estimated at possibly 300

1Highlights of 75 years in Mobile, Mobile, Alabama, First National Bank of Mobile, 1940, pages 6 and 7

2Highlights of 75 years in Mobile, Mobile, Alabama, First National Bank of Mobile, 1940, pages 6 and 7

My home town…Mobile…

Submitted by GW Jones (not verified) on 21 January 2014 – 10:30am.

During a portion of the construction of the George Wallace twin tunnels beneath the Mobile River from (1969-1973) I was a student/archaeological field assistant with the University of South Alabama. During what was termed “salvage archaeology” of the construction site, overseen by USA’s archaeology dept,we uncovered a variety of munitions relative to the 1865 explosion. They ranged from cannon balls to several examples of artillery shells. In a number of cases they were still considered “live” and capable of exploding. In those instances we asked the assistance of local police and military bomb disposal units to render the shells harmless. However, during that time, a number of “relic” hunters accessed the site and made off with several unexploded shells. A warning was issued through the local news and media outlets of the danger to anyone possessing the shells. Fortunately, many were returned before any potentially deadly events happened. Whether all were returned I do not know. Hopefully, no one today has one sitting on a mantle or display case.

The twin tunnel excavations resulted in a vast number of artifacts, representing nearly 400 years of occupation by Spanish, French, English and Americans, being unearthed. Many, I assume, are on display at the Mobile City and Fort Charlotte Conde’ museums.

GW Jones

More likely ended on April 26th, 1865 when General Johnston surrendered at Greensboro, N.C. The President of the Confederacy, Jeff Davis, was still running through Georgia on his way to Texas to continue the fight. A more accurate description of Lee’s surrender was the war was “realistically over”.

Gen. Lee surrendered at Appamatox April 9 of ’65

Terrific, little-known information about Mobile. Actually, the Civil War did NOT “officially” end when Lee surrendered. It went on for several months. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia, which had dwindled from about 80,000 at peak strength to about 28,000 at Appomattox. Thanks for posting.

The word official came from the news article I sourced but you are correct. It went on for awhile so I took out “officially”.

Robert Chapman

Lee’s surrender was not he end of the war, first Sherman had to run down General Joseph Johnson’s Army of Tennessee though the Carolina s and accept his surrender and there were some holdouts in the the west as well.

Lee’s surrender was the end of the Confederates last best chance but no quiet the end of the war.

Some “Seeshesh” remnants, so I hear, still lurk & slink in the swamps of back country Florida..but it’s probably only a rumor? You reckon?.

Hell yeah, I see their colors all the time!

The de facto end came with Lee’s surrender of the army of Northern Virginia there were other large armies in the field and other battles yet to be fought. “Officially” the end came in April 1866 when President Johnson issued his proclamation that hostilities had ended. Perhaps the most dramatic moment was at Appomattox it was yet awhile before the killing stopped. Thanks for the posting but don’t call it the “official end”.

Nice article, but the ‘official’ end of the war was not on April 9, 1865, with the surrender of Lee’s army. There were still two more large army’s in the field – Johnston’s Army of the Tennessee and Kirby Smith’s Army of the West. The last land battle of the war was a Confederate victory, at Palmito Rance in Texas in May of 1865. The last Confederates force to Surrender was the crew of the CSS Shenendoah several months later.

Here in Alabama. ..Clay county…they are still posting the guard

The Civil War did NOT officially end with Lee’s surrender at Appomattox as every student of the war knows. The Confederate government wasn’t recognized as legitimate by the U.S. and an official surrender couldn’t be signed by anyone, only individual armies could surrender. General Johnston’s troops, a larger force than Lee’s, surrendered to Sherman in N.C. April 26 and other generals during the weeks to come. On May 9, President Andrew Johnson declared that armed resistance had “virtually ended”. On May 12, troops in North Georgia finally surrendered. Word traveling slowly, one battle was fought in Texas on May 13. An official proclamation ending the war was finally ordered on August 20, 1866 by Pres. Johnson and Wm. Seward.

Finally, someone else that knows and understands history. Apparently, those writing these articles know less about it than a child. Some intentionally distort history, others do it through ignorance.

I’m not judging Pioneers intentions. The word “officially” should just be replaced with “virtually”. Appomattox is normally marked as the war’s end, but is actually more of the “beginning of the end”. As word of Lee’s decision to surrender spread (the CSA gov. had ordered him to keep fighting), other generals accepted the generous terms that Lincoln and Grant had agreed to.

My ggg-grandfather, Wade Lang of Guntersville, btw, was at Appomattox, one of the few members of the 9th Alabama left. Even though he lost his arm at Williamsburg in 1862, he went back into service at some point and was a teamster for Lee’s army.

Thank you for the clarification Charles. i picked up the word officially from the sourced news article. That is what is good about the internet. We can correct historical information.

My great grandfather’s brother, Andrew Reaney, was killed in the explosion. Hi wife, Caroline, their daughter, and newborn son returned to New Orleans, but Caroline died two years later, and the children, Andrew and Caroline, were adopted. Both children married, and had children of their own.

I have not been able to find a detailed list of Confederate soldiers who were killed in the explosion. Can anyone point me in the right direction?

Thanks!

David Maxwell

The Alabama State Archives may be able to help.

Thank you Donna. I did finally find a newspaper reference to his death in the June 4, 1865 New Orleans Times (apparently not the Times Picayune). I ordered a copy from the New Orleans Public Library Archives. It was a very brief two line statement

” Killed on the 25th of May, at the explosion in Mobile, ANDREW REANEY, aged 30 years, and a resident of Algiers (New Orleans).”

I have also been able to track down the descendants of his two orphaned children, however, I have not yet made contact with them.

David

[…] Engraving of the aftermath of the explosion in Mobile, Alabama, in which an estimate 300 people died. Courtesy of Alabama Pioneers. […]

[…] Gunpowder explodes in warehouse at Mobile and destroys half the town. [pictures & list of wounded soldiers] […]