General Sam Dale gives an eyewitness account of Shawnee Chief Tecumseh’s visit to Alabama in 1811

Scroll down to read story

The Shawnee chief, Tecumseh, came among the Native Americans in the south to incite them to hostilities against the whites. He was the emissary of the British, with whom the federal government was at war. The Spaniards at Pensacola and Mobile had already bred ill-feeling among them against the whites, and the fiery eloquence of Tecumseh precipitated the conflict of the Creek-Indian War.

In 1811, General Samuel Dale attended a grand council of the Creek Indians when Tecumseh appeared. He describes the event and even recorded Tecumseh’s speech in the Life and Times of Gen. Sam Dale: The Mississippi Partisan, Harper & Brothers, 1860.

Excerpt from General Samuel Dale’s report

In 1808, the State of Georgia distributed by lottery a large body of land acquired from the Creek Indians. I drew an excellent water-power, the Flat Shoals, on Commissioner’s Creek, and erected a set of mills; but the calling was not to my liking, and I disposed of them, and opened a farm in Jones County, which was for several years my home.

In October, 1811, the annual grand council of the Creek Indians assembled at Tooka-batcha, a very ancient town on the Tallapoosa River. At those annual assemblies the United States Agent for .the Creeks always attended, besides many white and halfbreed traders, and strangers from other tribes.

Five thousand people met at Took-a-batcha

I accompanied Colonel Hawkins, the United States Agent. A flying rumor had circulated far and near that some of the Northwestern Indians would be present, and this brought some five thousand people to Took-a-batcha, including many Cherokees and Choctaws.

The day after the council met, Tecumseh1, with a suite of twenty-four warriors, marched into the centre of the square, and stood still and erect as so many statues. They were dressed in tanned buckskin huntingshirt and leggins, fitting closely, so as to exhibit their muscular development, and they wore a profusion of silver ornaments; their faces were painted red and black. Each warrior carried a rifle, tomahawk, and war-club. They were the most athletic body of men I ever saw. The famous Jim Bluejacket was among them.

He was six feet tall

Tecumseh was about six feet high, well put together, not so stout as some of his followers, but of an austere countenance and imperial men. He was in the prime of life.

The Shawnees made no salutation, but stood facing the council-house, not looking to the right or the left. Throughout the assembly there was a dead silence.

At length the Big Warrior, a noted chief of the Creeks and a man of colossal proportions, slowly approached, and handed his pipe to Tecumseh. It was passed in succession to each of his warriors; and then the Big Warrior—not a word being spoken— pointed to a large cabin, a few hundred yards from the square, which had previously been furnished with skins and provisions. Tecumseh and his band, in single file, marched to it.

He would talk the next day

At night they danced, in the style peculiar to the northern tribes, in front of this cabin, and the Creeks crowded around, but no salutations were exchanged. Every morning the chief sent an interpreter to the council-house to announce that he would appear and deliver his talk, but before the council broke up another message came that “the sun had traveled too far, and he would talk next day.

At length Colonel Hawkins became impatient, and ordered his horses to be packed. I told him the Shawnees intended mischief; that I noted much irritation and excitement among the Creeks, and he would do well to remain. He derided my notions, declared that the Creeks were entirely under his control and could not be seduced, that Tecumseh’s visit was merely one of show and ceremony, and he laughingly added, “Sam, you are getting womanly and cowardly.”

Tecumseh marched around the square

I warned him that there was danger ahead, and that, with his permission, as I had a depot of goods in the nation, I would watch them a while longer. We then packed up and publicly left the ground, and rode twelve miles to the Big Spring, where Colonel Hawkins agreed to halt for a day or two, and I returned at night to the vicinity of the council ground, where I fell in with young Bill Milfort, a handsome half-blood, nearly white, whom I had once nursed through a dangerous illness. Bill—alas! that he should have been doomed to perish by my hand —was strongly attached to me, and agreed to apprise me when Tecumseh was ready to deliver his talk.

Next day, precisely at twelve, Bill summoned me. I saw the Shawnees issue from their lodge; they were painted black, and entirely naked except the flap about their loins. Every weapon but the war-club—then first introduced among the Creeks—had been laid aside.

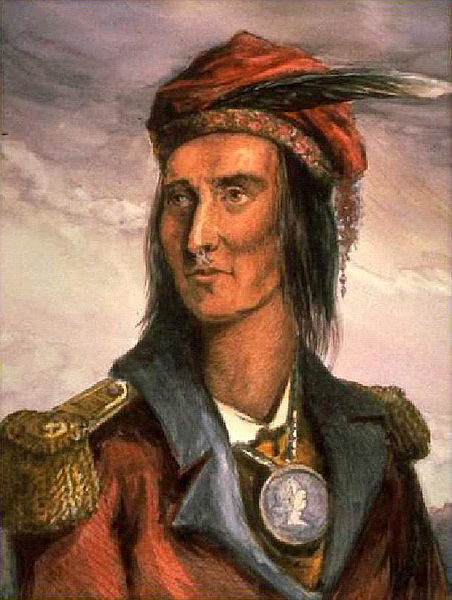

Tecumseh from engraving 1861 (Library of Congress)

Tecumseh from engraving 1861 (Library of Congress)

An angry scowl sat on all their visages: they looked like a procession of devils. Tecumseh led, the warriors followed, one in the footsteps of the other. The Creeks, in dense masses, stood on each side of the path, but the Shawnees noticed no one; they marched to the pole in the centre of the square, and then turned to the left.

At each angle of the square Tecumseh took from his pouch some tobacco and sumach, and dropped it on the ground; his warriors performed the same ceremony. This they repeated three times as they marched around the square. Then they approached the flag-pole in the centre, circled round it three times, and, facing the north, threw tobacco and sumach on a small fire, burning, as usual, near the base of the pole. On this they emptied their pouches.

They then marched in the same order to the council, or king’s house (as it was termed in ancient times), and drew up before it. The Big Warrior and the leading men were sitting there.

Gave the Shawnee pipe to Big Warrior

The Shawnee chief sounded his war-whoop—a most diabolical yell—and each of his followers responded. Tecumseh then presented to the Big Warrior a wampum-belt of five different-colored strands, which the Creek chief handed to his warriors, and it was passed down the line.

The Shawnee pipe was then produced; it was large, long, and profusely decorated with shells, beads, and painted eagle and porcupine quills. It was lighted from the fire in the centre, and slowly passed from the Big Warrior along the line.

All this time not a word had been uttered; every thing was still as death: even the winds slept, and there was only the gentle rustle of the falling leaves.

He spoke slowly at first

At length Tecumseh spoke, at first slowly and in sonorous tones; but soon he grew impassioned, and the words fell in avalanches from his lips. His eyes burned with supernatural lustre, and his whole frame trembled with emotion: his voice resounded over the multitude—now sinking in low and musical whispers, now rising to its highest key, hurling out his words like a succession of thunderbolts.

His countenance varied with his speech: its prevalent expression was a sneer of hatred and defiance; sometimes a murderous smile; for a brief interval a sentiment of profound sorrow pervaded it; and, at the close, a look of concentrated vengeance, such, I suppose, as distinguishes the arch-enemy of mankind. I have heard many great orators, but I never saw one with the vocal powers of Tecumseh, or the same command of the muscles of his face.

Had I been deaf, the play of his countenance would have told me what he said. Its effect on that wild, superstitious, untutored, and warlike assemblage may be conceived: not a word was said, but stern warriors, the “stoics of the woods,” shook with emotion, and a thousand tomahawks were brandished in the air.

Even the Big Warrior, who had been true to the whites, and remained faithful during the war, was, for the moment, visibly affected, and more than once I saw his huge hand clutch, spasmodically, the handle of his knife.

All this was the effect of his delivery; for, though the mother of Tecumseh was a Creek, and he was familiar with the language, he spoke in the northern dialect, and it was afterward interpreted by an Indian linguist to the assembly. His speech has been reported, but no one has done or can do it justice. I think I can repeat the substance of what he said, and, indeed, his very words. (Tecumseh’s speech as related by Samuel Dale plus more stories can be found in ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS – Pioneers: Lost & Forgotten Stories )

1At the battle of the Holy Ground, which occurred some time after, the prophets left by Tecumseh predicted that the earth would yawn and swallow up General Claiborne and his troops. Tecumseh refers to the Kings of England and Spain, who supplied the Indians with arms at Detroit and at Pensacola. The British officers had informed him that a comet would soon appear, and the earthquakes of 1811 had commenced as he came through Kentucky. Like a consummate orator, he refers to them in his speech. When the comet soon after appeared, and the earth began to tremble, they attributed to him supernatural powers, and immediately took up arms.

Very interesting story ! I didn’t know he went south

My, “real name” is, David E. McKenzie

“[email protected]” is my “Email” address.