In the 1830s many Native-Americans were divided in their opinions about moving west. Some voluntarily moved with the first treaties, and others delayed in their old homes until forced to remove by the encroachment of white settlers, and the power of the federal government.

Others continued their residence in their old homes even if it meant accepting the white European way of life.

Volunteers looked for a better future

Those that voluntarily left rejoiced at the prospect before them, but they saw it as their only option to continue their life as hunters. Game was scarce and the hunter life was restricted on the east side of the Mississippi. They knew that if they stayed, their hunting culture would disappear and they were facing extinction. There was no other choice but to leave.

Yoholomicco sold a half-section of land to Richard S. Ware for One Thousand Dollars, and prepared to leave Alabama forever.

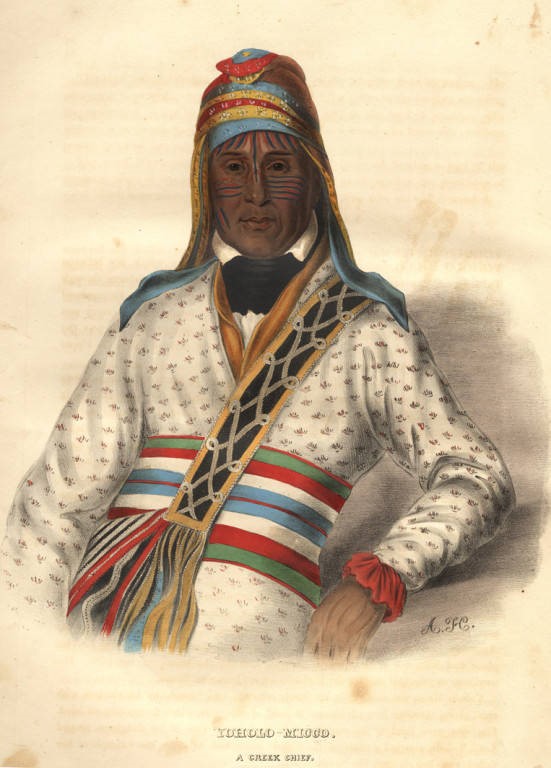

Yoholomicco was a Creek Chief, born about 1788. Nothing has been recorded as to his parents, his early life, nor when he became chief of Yufala and Speaker of the Creek Nation. There were two towns named Yufala in the Upper Creek country; the one, of which Yoholomicco was chief, was situated on the west bank of the Tallapoosa, two miles below Okfuskee.

Served with General McIntosh

Yoholomicco. also known as Chief Eufaula, had served with General Mclntosh in the Creek war of 1813 and bore an honorable part in all the battles in which the friendly Creeks were engaged against their insurgent countrymen. He was delegate from his nation to Washington in 1826 and he was greatly instrumental in negotiating the treaty of November 15, 1827, by which the Creeks ceded the last of their lands in Georgia.

As Speaker of the Council convened to hear the propositions of the government on that occasion, his demeanor is thus described by Colonel Thomas L. McKenny, there present representing the government, and a most competent eye witness:

“Yoholo Micco explained the object of the mission, in a manner so clear and pointed as not to be easily forgotten by those who heard him. He rose with the unembarrassment of one, who felt the responsibility of his high office, was familiarly versed in its duties, and satisfied of his own ability to discharge it with success. He was not unaware of the delicacy of the subject, nor of the excitable state of the minds to which his argument was to be addressed, and his harangue was artfully suited to the occasion. With the persuasive manner of an accomplished orator, and in the silver tones of a most flexible voice, he placed the subject before his savage audience in all its details and bearings—making his several points with clearness, and in order, and drawing out his deductions in the lucid and conclusive manner of a finished rhetorician.”

Dangerous and sad journey

Their journey was long, hard, and dangerous to their eventual destination – Arkansas. Rivers, swamps, and mountains were to be crossed. Many children .were on foot, and old men, too feeble to walk, had to be transported.

When the Creeks reached Tuscaloosa, the Alabama State Legislature was meeting. Before the house adjourned, they were informed of the large party of the Creeks camped near Tuscaloosa, under the conduct of Col. Hunter, the agent, with the principal chief of the nation named Eufaula.

The description and contents of the event was published in the Huntsville, Alabama Democrat and also the Niles Weekly Register in 1835. Despite the obstacles faced ahead, Chief Eufaula presented a voice of optimism.

A motion was made by Mr. Jackson to invite the chief and his warriors within the bar of the house which was agreed to unanimously. Mr. Jackson was then instructed to convey the invitation of the house. The chief agreed to speak, and he and his warriors were conducted in and they seated themselves in chairs arranged around the hall below the lower tier of desks.

Chief Eufaula, addressed the house from his seat in substance pretty much as follows—he spoke in the Creek language, which was interpreted from time to time as he proceeded by Col. Hunter.. The effect upon the house and gallery was solemn and interesting. The tear started in more eyes than one. The chief is an Indian of fine appearance-his aspect grave his voice low and subdued—his words slow. He proceeded:

“I come brothers to see the great house of Alabama, and the men that make the laws, and tell them farewell in brotherly kindness before I go to the far west, where my people are now going. I did think at one time that the white man wanted to oppress my people and drive them from their homes by compelling. them to obey the laws that they did not understand—but I have now become satisfied that they are not unfriendly towards us, but that they wish us well. In these lands of Alabama, which have been my forefather’s, where their bones lie buried, 1 see that the Indian fires are going out—they unjust soon be extinguished. New fires are lighting in the west—and we will go there. I do now believe that our great father, the president, intends no harm to the red men—but wishes them well. He has promised us homes and hunting ground in the far west, where he tells us the red men shall be protected. We will go. we leave behind our good will to the people of Alabama, who build the great houses, and to the men who make the laws.

“This is all I have to say—I came to say farewell to the wise men who make the laws, and to wish them peace and happiness in the country which my forefathers owned and which I now leave to go to other homes in the west. I leave the graves of my fathers—but the Indian fires are going out—almost clean gone—and new fires are lighted there for us. “There are two houses of the men who make the laws—I have already bid farewell to the other house—I now bid farewell to you, and wish not only you, but all the people of Alabama, to be happy and prosperous. I leave you in friendship and good will. I have nothing more to say.”

When Eufaula concluded, there was a peal of applause through the house and gallery.

The speaker replied in a handsome and appropriate manner to the address of the chief—briefly adverting to the cause of the extension of our jurisdiction and stating the advantages of a removal, to the Indian tribes. After which the members rising from their seats, as a token of respect, the chief and his warriors retired. The reply of the speaker was interpreted to the chief by one of the chiefs, a half breed, by name Grayson.

Indeed, sir, it was an affecting scene and forced upon the minds of the spectators a current of recollection that carries something of a pang to the heart of the white man.

Chief Yoholo Micco never made it to Arkansas. He died en route. A historical marker in Tuscaloosa, Alabama marks the date and remembers his speech that was so full of hope for the Creek Nations’ future.

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Banished: Lost & Forgotten Stories (Volume 8)

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Banished reveals true stories, documents and news articles from this sad time in Alabama’s history. Some stories include:

Choctaw & Treaty Of Dancing Rabbit Creek

Private Contracts For Removal

Stockades In Alabama

The Long Trail West

Reverend Daniel S. Burtrick’s 1838 Journal

An Observer Writes His Memories