SUNDAY OBSERVANCE IN ALABAMA

Sunday,

On March 12, 1803, the Legislative council and House of Representatives of that Territory, of which the present State of Alabama was then in part the eastern half, enacted that “no worldly business or employment, ordinary or servile works (works of necessity or charity excepted), no shooting, sporting, hunting, gaming, racing, fiddling, or other music for the sake of merriment, nor any kind of playing, sports, pastimes, or diversions, shall be done, performed or practiced, by any person or persons within this Territory on the Christian sabbath or first day of the week, commonly called Sunday.”

It is further provided that “no merchant or shop keeper or other person, shall keep open store, or dispose of any wares or merchandise, goods or chattels on the first day of the week, commonly called Sunday, or sell or barter the same.” The act further provides “that no wagoner, carter, drayman, drover, butcher, or any of his slaves or servants, shall ply or travel with his wagon, cart or dray, or shall load or unload any goods, wares, merchandise or produce, or drive cattle, sheep or swine in any part of the Territory, on the first day of the week called Sunday.” The service or execution of writs and processes, except in criminal cases was prohibited. Penalties were provided for violations of the foregoing regulations.—Toulmin’s Digest, pp. 216-217.

The foregoing in varying forms has been on the statute books of Alabama from that day to this, and is now to be found as Chapter 295 of the Criminal Code, 1907, Vol. 3.

This act appears in Toulmin’s Digest, 1823, as of full force and effect with the beginning of statehood. From time to time it has undergone modification and restatement. The number of prohibited acts has been enlarged, as the keeping of open bar rooms, or other places for the sale of spiritous, vinous, or malt liquors, or the sale on Sunday of such liquors, by act of February 23, 1903, p. 64. The same Session of the legislature, September 28, 1903, p. 281, passed a law prohibiting any person from playing or engaging in playing baseball, football, tennis or golf on Sunday, “in any public place or places where people resort for such purpose.”

Modifications of the Statute through 1919

The modifications of the statute referred to have not in any way robbed it of its original purpose and present intent of protecting the sabbath day from desecration by the doing of prohibited acts. Even those sects or religious organizations which do not recognize the first Jay of the week, are held by our courts to have no constitutional right to do Sunday work. It is proper to observe that the sacredness which attaches to the observance is not predicated upon the theory that Sunday is a religious institution, but upon general principles of sanctity.

It is further to be observed that the

The law further provides that “all contracts made on Sunday, unless for the advancement of religion, or in the execution, or for the performance of some work of charity, or in case of necessity, or contracts for carrying passengers or perishable freight, or transmissions of telegrams, or for the performance of any duty authorized or required by law to be done on Sunday are void.”

In the interpretation of this section the courts have been strict in carrying out its intent and purpose, namely, to prohibit the carrying on of business or secular transactions on Sunday. It has rigidly declined to enforce contracts made on Sunday, and they have been declared incapable of enforcment.—101 Ala. 162. It has been held that a note or contract dated or agreed to on Sunday but shown to have been made on “a secular day is valid, but it is absolutely void if dated on a secular day and made on Sunday.—96 Ala. 609; 76 Ala. 339; 87 Ala. 334.

As illustrating works of necessity, a verdict may be received on Sunday, judgment being entered afterwards.—78 Ala. 466. A bail bond may be issued on Sunday.—59 Ala. 164. A telegram announcing the death of a relative is a necessity, and may be sent and delivered.—93 Ala. 32. Service of legal process on Sunday is not one of the acts forbidden by statute.—50 Ala. 384.

(Code of Ala., Vol. 2, 3346.)

The statute expressly provides that “attachments may issue and be issued on Sunday, if the plaintiff, his agent or attorney, in addition to the oath prescribed for the issue of such process, make affidavit that the defendant is absconding, or is about to abscond, or is about to remove his property from the State and give the bond required.” Code, Vol. 2, Sec. 2938. Reid vs. State, 53 Ala., p. 408, is now changed by the statute.

Sunday is dies non juridicus.—74 Ala.; 84 Ala., 432; 87 Ala., 91; 101 Ala., 162. Sunday is the only legal holiday-that is so regarded. All other legal holidays, named in Sec. 5144 and amendatory statutes thereto occupy different relations.—Code of Ala., Vol. 2, p. 1099.

The Code of 1852 contains this provision:

“The time within which any act is provided by law to be done, must be computed by excluding the first day and including the last; if the last day is Sunday it must also be excluded.” Sec. 13, p. 59.

This section remains the law to this day, Sec. 11, Code, 1907, Vol. 1. * However, this Code contains the additional provision that “the Monday following shall be counted as the last day within which the act may be done.”

The courts have been appealed to for various applications of the rules stated in this section. To illustrate: If an act is to be done within a given time after adjournment of court, the first day after adjournment must be, excluded.—119 Ala. 459. If an act is to be done within thirty days from the 29th of November^ the time expires on the 29th of December; if that day be Sunday, the act cannot be performed on the Monday following, but should be done on Saturday preceding the last day.—136 Ala. 418.

For illustration of the exclusion of the first and including the last day consult 69 Ala., 221; 78 Ala., 403; 80 Ala., 308; 89 Ala., 406; 90 Ala., 68.

If the last day of the limitation is Sunday, action brought on the following Monday is barred.—67 Ala., 4 33. See Mayfield’s Digest, Vol. 4, p. 945.

Somerville, Judge, 67 Ala., p. 437, says, with reference to Sec. 11:

“The statute we think was intended merely as a reaffirmation of the common law rule, that while Sundays are generally to be computed in the time allowed for the performance of an act, if the last day happens to be Sunday, it is excluded and the act must be performed on the day previous.—See 2d Vouvier Law Dictionary, title “Sunday.”

SOURCE

(Transcribed from History of Alabama and dictionary of Alabama biography, Volume 2 By Thomas McAdory Owen, Marie Bankhead Owen -1919)

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS – Volume I – IV: Four Volumes in One

BUY ONE GET ONE FREE! The first four Alabama Footprints books have been combined into one book,

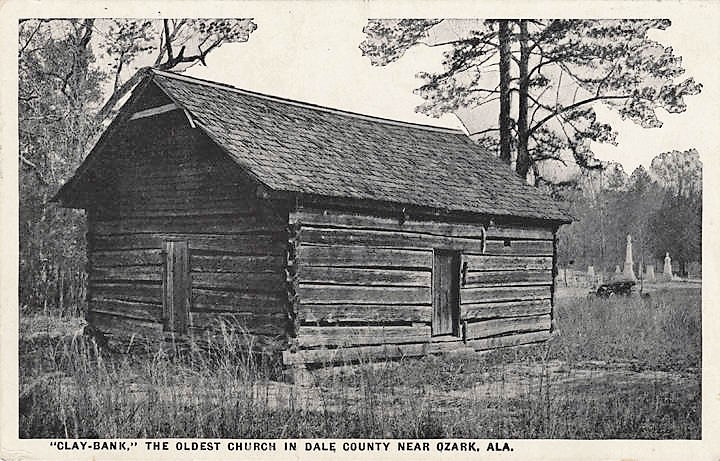

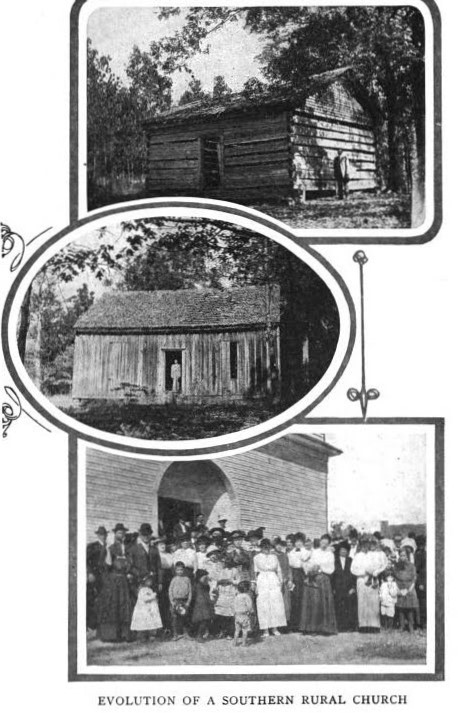

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Exploration

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Settlement

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Pioneers

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Confrontation

From the time of the discovery of America restless, resolute, brave, and adventurous men and women crossed oceans and the wilderness in pursuit of their destiny. Many traveled to what would become the State of Alabama. They followed the Native American trails and their entrance into this area eventually pushed out the Native Americans. Over the years, many of their stories have been lost and/or forgotten. This book (four-books-in-one) reveals the stories published in volumes I-IV of the Alabama Footprints series.