LATER HISTORY OF MADISON COUNTY

By Thomas Jones Taylor

(Judge Taylor’s “Early History of Madison County” was concluded in the Spring, 1940, issue of the Alabama Historical Quarterly. This installment is the second of his “Later History of Madison County”, the first being in the Summer, 1941, issue of the Quarterly. This article first appeared in the Huntsville Independent, in 1883 and 1884.)

Chapter V

Clearing the Lands.

When our fathers came to this county it was everywhere covered with a magnificent growth of timber. Except the Chickasaw Old Fields around Whitesburg and the one solitary prairie on the Rice plantation north of Triana, which did not cover half a section of land, the forests were in their primeval state; and in order to prepare and fit the soil for farming purposes it was necessary that the land should be cleared of the gigantic forest trees that shut out the life-giving rays of the sun from the surface of the soil.

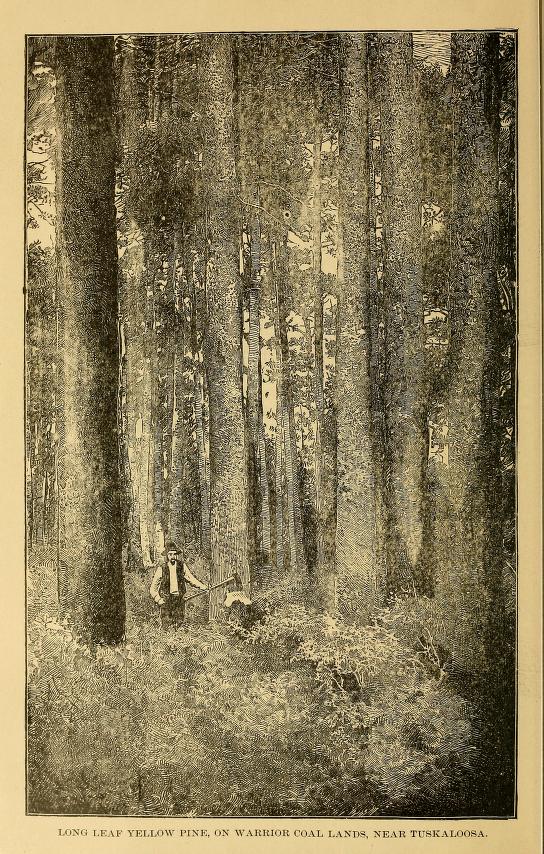

A drawing of forest 1887 around the City of Tuscaloosa, Alabama

Work was slow at first

In the first settlement, and until capital and slave-labor from the older States made this a possible task, the work had proceeded slowly, and a few acres here and there indicated the different settlements of the earliest pioneers in the county; and even when labor had become cheap and abundant in some part of the county, the destruction of the timber in the new grounds required many years of serious work. Girdling the timber on the new grounds was almost the universal practice and was called deadening, and a tract of land where the trees were girdled and the land not fenced or cultivated was known as a “deadening” Trees deadened in August and September did not put forth any more leaves, and by the following spring cultivation of the land might commence with a prospect of a partial crop, though cultivating such land was generally rough work, as the roots of the trees, so thickly interwoven in the soil, made thorough cultivation and a fair return for the labor performed impossible.

The timber was very seldom cut and hauled off the land, as most farmers were of the opinion that land was better on which the forest growth was allowed to remain and gradually decay. In old Madison, where large tracts of land were taken up and clearing was undertaken on a large scale, the landowners with their stalwart slaves and strong oxen and horses were able to girdle and fence large tracts in comparatively a short period of time, but the work awaiting a solitary laborer with his forty or eighty acres of virgin land covered with giant forest growth, involving the labor of clearing and fencing enough land to support his family, was a task at once arduous and laborious.

Primeval forest is gone

At the time of which I wrote, especially east of the mountains, a large number of small farmers were clearing lands-afterwards consolidated into larger farms, and their labor fitted for cultivation many of the clean, fertile fields on which, to-day, can be seen not the least vestage (sic) of the primeval forest that once thickly covered them.

After the first year’s cultivation, the tall poplars and sturdy oaks, in process of decay, began to drop their smaller branches, and by the opening spring the earth was covered with their debris, that must be gathered and burnt before plowing began. In the course of another season the winds of winter prostrated the less durable and the smaller trees, and log-rolling commenced. At first this labor was not so heavy, as the logs were small and easily managed, and in a few years the taller and more durable trees, divested of bark and smaller limbs, the skeletons of the once living forest, remained. But the timber was so dense that there were immense numbers of these dead trees standing, and when, in course of time, the winds prostrated their huge trunks, their removals was a herculean task, requiring from one to two months’ hard labor in the beginning of the farming season.

Community worked together to remove trees

Among the settlements of smaller farmers during log-rolling time, there was by common consent a community of labor. Every family was expected to furnish at least one good hand for a month’s or six weeks’ labor, and when his log-rolling day came round he expected his neighbors in person or by proxy to be on hand for business. The oak and popular timber was notched at intervals of ten or twelve feet on the logs and fire kindled on them, which being built up morning and eventually, soon gnawed its way through and severed the prostrate trunk into convenient lengths for rolling. Hickories of large size were very heavy, but fortunately when partly seasoned and once ignited they were generally consumed entirely.

Just before log-rolling day, the farmer with his sharp axe inspected his new ground and severed all cuts not entirely cut off by the fire, as it was considered bad management to delay a score of men in chopping up logs on log-rolling day. It was wonderful to behold how a force of stalwart, experienced farmers would pile up the logs over acre after acre of fallen timber. They would approach the several cuts of a log, oak or poplar, stretching for sixty or seventy feet on the ground, inspect it a moment, divide into squads, turn a cut here and there into proper position, and almost as quick as though two or three large log heaps would take the place of the prostrate timbers.

From sunrise until sunset, with a single hour’s rest at noon, the work would go on, or until the job was completed, and every man was expected to dine and sup with his neighbor who was furnishing the day’s work.

There were giants in those days, the loads the men carried with their long dogwood hand-spikes were wonderful; sometimes the logs were so large that when raised the men on either side could scarcely see over them, and to the bystander it presented the novel spectacle of a big log moving off with a row of men on one side. In this business, by long practice, our ancestors acquired a peculiar sleight in grasping the hand-spike, in balancing the body, and keeping proper step in bearing the unwieldy burden. From this branch of labor originated the phrase of “toting fair”, as between men of nearly equal strength an inch or two difference in the divide of a stick gave great advantage, and where a strong man matched a weaker one it was expected to neutralize the difference in dividing the leverage of the hand-spike.

Used fire to clear lands

The old settlers made the use of fire a valuable auxiliary in clearing up the lands in the spring, but sometimes it turned to a dangerous foe. In the spring, which in those days was generally early and warm, the logs in the fields would be piled, and through an entire settlement the logs would be fired nearly at the same time, and at night the face of the whole community would be illuminated by the blazing heaps.

If the season was unusually dry, the sap of the standing timber would ignite and burn like tinder. Sometimes the wind would rise and the flying sparks would set the dead forest on fire, and the farmers would have to fight for their fences and fodder stack through the entire night among the fire and smoke and blazing and falling branches and trunks of the burning trees. A blazing fire-brand would fall on the dry fence, the watchful farmer would come to the rescue and the rails would be scattered to the right and left out of the reach of the flames, and the danger would hardly be averted before he would have to hasten to some other point of danger.

These conflagrations would sometimes spread from field to field and the whole neighborhood would come to the rescue. During the winter the dark forests would drop a thick covering of leaves over the surface of the earth and they, becoming dry in the spring would accidentally or designedly be set on fire. This fire would probably start on the mountains and night after night the bright fiery circles would increase in area until a rise or change in the wind would send them speeding down the valleys, and when they got among the canebreaks the popping of the cane would be like the collision of the skirmish lines of opposing armies.

As the flames approached their fields the owners would clear long paths round their enclosures and fire would fight fire, the slower line of flame would meet the faster, and with a brilliant glare on meeting would die out along the whole opposing line and the danger would be over for a season. From the first fencing of the lands until the disappearance of the original forest growth was a period of many years and involved an immense amount of manual labor. Timber at that time was of little value and to our fathers the supply seemed inexhaustible, and the amount wantonly destroyed on lands of but little agricultural value was enormous. A large area of land was cleared by non-land owners, who would take leases on forty or eighty tracts which they would clear and fence on which they would erect cabins, for the use and occupancy of the lands for from five to seven years.

Great dexterity

I can recollect many wealthy and prosperous farmers of the olden time who started in business on such leases of land, of which by years of industry and thrift, they finally became owners. From long experience and labor in making rails to fence these lands and building their tenements the early settlers attained wonderful dexterity in the use of the maul and axe, and we have authentic evidence of a single laborer splitting one thousand rails between sunrise and sunset. With a heavy Collin’s axe with a helve four feet long of strong white hickory, they tackled the immense forest trees, and in an incredibly short period of time they would fell and chop them into convenient lengths for rails or boards.

While it was necessary for agricultural purposes that the forest growth should be removed, yet it was a great calamity that the timber should have been wantonly destroyed on lands comparatively barren, on which the timber would finally have been incalculably of more value than all the land ever produced. It is possible that denuding the land of its forest growth has made the country healthier, by removing decayed vegetable matter, that was once a fruitful source of disease, and in causing the filling up and placing in cultivation of what were once in summer stagnant ponds and lagoons, and in removing the causes of obstructions in our creeks and rivers and thus improving the drainage. Yet aside from the immense pecuniary loss to our people the wholesale destruction of our forests has in many other respects inflicted serious injury upon our county.

As a consequence of the destruction of our forests, the seasons are more uncertain, springs that once furnished an abundance of water throughout the year have failed, the annual rainfall diminished and drought is more frequent. When we see the settlers on the western prairies, by judicious timber culture, restoring the forest growth and know the success of their efforts in that direction, we are convinced that the time has arrived for our people to attend to the preservation of the remnants of our once magnificent forests, and also to restore the forest growth on their worn and useless land by the planting and culture of forest trees.

You’re in for a treat! Make sure you don’t miss out on the captivating novel by Donna R Causey. Get your hands on it today!

Tapestry of Love: Three Books In One – Historical fiction by DONNA R CAUSEY

REVIEWS

The exhilarating action & subplots keep the reader in constant anticipation. It is almost impossible to put the book down until completion,

Dr. Don P. Brandon, Retired Professor, Anderson University, Anderson, Indiana

This is the first book I have read that puts a personal touch to some seemingly real people in factual events.

Ladyhawk

Love books with strong women…this has one. Love early American history about ordinary people…even though they were not ‘ordinary’…it took courage to populate our country. This book is well-researched and well-written.