Excerpt from ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS: Confrontation (Story continued below)

Become an Alabama Pioneers Patron

JOIN US FOR FREE

Cancel anytime

A Warning Saves Many Lives

In 1812, the long-threatened war between the United States and Great Britain was formally declared. At the beginning of the war, the Americans had asserted their title to the town and harbor of Mobile, which, although a part of the territory ceded many years before to the United States by the French, had until now been held by the Spanish.

The affair was so well managed that the place was surrendered without bloodshed and occupied by the American forces. However, its surrender created hostility among the Spanish in Florida, and even though America was at peace with Spain, the Spanish authorities at Pensacola readily lent themselves to the schemes of the British. In 1812, they had even allowed a British force to land at Pensacola, take possession of the fort there, and make it a base of operations against the United States.

The Spanish also assisted the Native Americans by providing parties of Indians who visited them to trade for arms and ammunition to use against Americans.

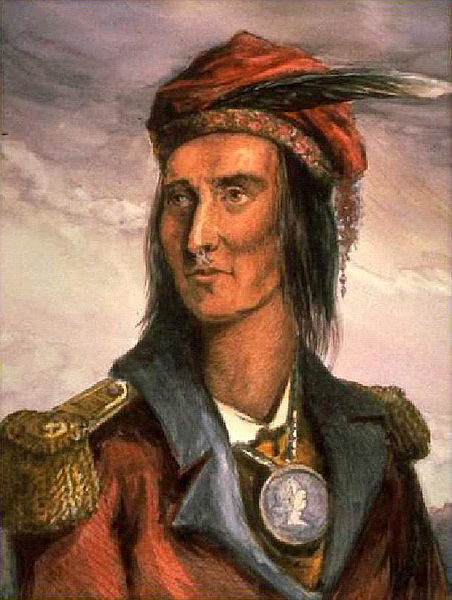

After Tecumseh’s visit, a friendly Indian by the name of Sam Moniac was driven from his home and his cattle was taken to Pensacola to be sold by a marauding warring party. He hid in the swamps for awhile, then finally ventured out at night to visit his home. where he met High Head Jim who was at the head of some hostile Indians. In order to save his life, he lied and told the hostile party that he had given up his peaceful beliefs and had made up his mind to join the war party.

He related his frightening experience in the a deposition taken in 1813 as follows:

About the last of October, 1812, thirty northern Indians came down with Tecumseh, who said he had been sent by his brother, the Prophet. They attended our council at the Tuccabache, and had a talk for us. I was there for the space of three days; but every day, while I was there, Tecumseh refused to deliver his talk; and, on being requested to give it, said the sun had gone too far that day. The next day I came away, and he delivered his talk. It was not until about Christmas that any of our people began to dance the war-dance. The Muskhogees have not been used to dance before war, but afterward. At that time, about forty of our people began this “northern custom;” and my brother-in-law, Francis, who also pretends to be a “prophet,” was at the head of them.

Their number has very much increased since, and there are probably now more than one half of the Creek nation who have joined them. Being afraid of the consequences of a murder having been committed on the mail-route, I left my house on the road, and had gone down to my plantation on the river, where I remained some time. I went to Pensacola with some steers; during which time my sister and brother, who have joined the war party, came and took off a number of my horses, and other stock, and thirty-six of my negroes. About twenty-two days ago I went up to my house on the road, and found some Indians encamped near it, and I tried to avoid them, but could not. An Indian came to me, who goes by the name of High-headed Jim, and who, I found, had been appointed to head a party sent to Autossee town, on the Tallapoosa, on a trip to Pensacola. he shook hands with me, and immediately began to tremble and jerk in every part of his frame, and the very calves of his legs were convulsed, and he would get entirely out of breath with the agitation. This practice was introduced in May or June last by “the Prophet Francis,” who says that he was so instructed by the Spirit. High-headed Jim asked me what I meant to do. I said that I would sell my property, and buy ammunition from the governor; and join them. He then told me they were going down to Pensacola to get ammunition, and they had got a letter from a British general, which would enable them to receive ammunition from the governor; that it had been given to the Little Warrior, and was saved by his nephew when he was killed, and by him sent to Francis. High Head told me that, when they went back with their supply, another body of men would go down for another supply of ammunition; and that ten men were to go out of town, and they calculated on five horseloads for every town. He said they were to make a general attack on the American settlements; that the Indians on the waters of the Coosa, Tallapoosa, and Black Warrior were to attack the settlements on the Tombigby and Alabama, particularly the Tensas and Fork settlement that the Creek Indians bordering on the Cherokees were to attack the people of Tennessee, and that the Seminoles and Lower Creeks were to attack the Georgians; that the Choctas also had joined them and were to attack the Mississippi settlements; that the attack was to be made at the same time in all places, when they had become furnished with ammunition.

I found from my sister that they were treated very rigorously by the chiefs; and that many, especially the women, among them two daughters of the late General McGillivray, who had been induced to join them in order to save their property, were very desirous of leaving them, but could not.

I found from the talk of High Head that the war was to be against the whites, and not between the Indians themselves; that all they wanted was to kill those who had taken the talk of the white, viz: the Big Warrior, Alexander Curnells, Captain Isaac, William M’Intosh, the Mad Dragon’s son, the Little Prince, Spoke Kange, and Tallasee Thicksico. They have destroyed a large quantity of my cattle, have burned my houses and my plantation, as well as those of James Curnells and Leonard M’Gee.

(Signed) Samuel (his S. M. mark) Moniac

Sworn to and subscribed before me, one of the United States judges for the Misssisppi Territory, this 2d day of August, 1813. Harry Toulmin

(A true copy) George T. Ross, Lieutenant-colonel of Volunteer

High Head Jim believed him and began to tell him of their plans to kill the peaceful chiefs, which included Big Warrior, Captain Isaacs, McIntosh and Mad Dragon’s son. They believed that if the peaceful Creeks were deprived of their leaders, then those that remained would be compelled to join with the Red Sticks.

Once all the Creeks were united, they would begin the war by simultaneous attacks upon the white settlements. Having exterminated the whites upon their borders, they were to march in three columns against the people of Tennessee, Georgia, and Mississippi with assistance from the Choctaws and the Cherokees.

After High Head Jim and his party left, Moniac set out to inform the intended victims which enabled them to secure their safety. But the civil war increased in fury as hostile bands of Indians attacked the peaceful members of the Indian Nation, destroyed their houses, killed or drove off their cattle and stole their property.

In 1812, Congress responded to the violence taking place with the Native Americans and authorized the raising of a volunteer corps of fifty thousand men, to serve one year within two years after they were organized. General Andrew Jackson from Tennessee volunteered to lead men from Tennessee, and by November of 1812, a volunteer army of twenty-five hundred men joined him and were accepted as part of a national force.

The appearance of a British fleet off the Gulf coast awakened the American government to the danger in which Mobile lay, and on the 28th of June, 1813, Brigadier-General Ferdinand L. Claiborne, a distinguished soldier who had won a fine reputation in the Indian wars of the Northwest, was ordered, with what force he had, to march from the post of Baton Rouge to Fort Stoddard, a military station on the Mobile River, not far below the confluence of the Alabama and Tombigbee rivers.

“Upon receiving this order General Claiborne made application for the necessary funds and supplies, but the quartermaster could put no more than two hundred dollars into his army chest—a sum wholly inadequate to the purpose.”

“Claiborne was not a man to permit small obstacles to interfere with affairs of importance. He borrowed the necessary funds upon his personal credit, giving a mortgage upon his property as security, and boldly set out with his little army. It is worthwhile to note in passing that, in consequence of the loss of vouchers for his expenditures upon the expedition, General Claiborne’s patriotic act cost him the whole amount borrowed, his property being sold after his death, as we learn from a note in Pickett’s History of Alabama, to satisfy the mortgage.”

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Confrontation: Lost & Forgotten Stories Volume 4

is a collection of lost and forgotten stories that reveals why and how the confrontation between the Native American population and settlers developed into the Creek-Indian War as well as stories of the bravery and heroism of participants from both sides.

Some stores include:

- Tecumseh Causes Earthquake

- Terrified Settlers Abandon Farms

- Survivor Stories From Fort Mims Massacre

- Hillabee Massacre

- Threat of Starvation Men Turn To Mutiny

- Red Eagle After The War