Mahan boys and comrades

(Written in 1910)

The three Mahan boys and their comrades, following the good fight at New Orleans, split up into small crowds, “and,” writes Kevin Cunningham Mahan for this record, “rather than tackle the job of running boats on the Mississippi up stream, they decided to follow the not any too safe Indian trails, or just strike out right up through the woods of Mississippi Territory in the direction the wild geese flew in the spring of the year.”

Major Jonathan Mahan was bell wether

One party of these soldiers was composed of eighteen members under the leadership of Major Jonathan Mahan, who was their “bell wether,” so to speak. “Among them,” states Mr. Mahan, “were James and Edward Mahan, and Linzeys, Fanchers, Massingales, Ragans, and Smiths. They made a compromise of trails and directions, and, after following what was known as the Tuskaloosa trail, took to the woods. When they reached the confluence of three creeks, those known to-day as Mahan, Shoals, and Mayberry creeks, which together make the Little Cahaba River, they found here an Indian camp well stocked with swine, horses, cows, and corn; also, says rumor, there were here a goodly number of comely Indian maidens, and not too great a number of bucks with highly developed fighting proclivities.” Be that as it may, twelve of the soldiers of fortune, like Ulysses of old, here laid down their arms, cast in their lots with the Indians and were not again heard of. The other six, together with a few Indians and traders, continued on their way to the Cumberland Valley for their wives and children. Returning with a small gathering of friends, they founded on the fertile site of the little Indian village the settlement later known as Brierfield, and gave to the broad-flowing creek the name of Mahan’s Creek.

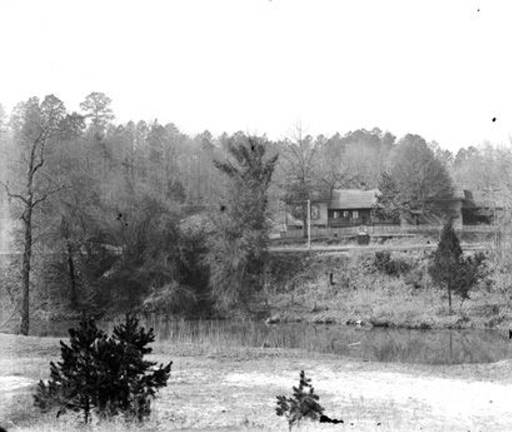

Brierfield, Superintendents house on Mahan Creek (Alabama Department of Archives and History)

Cahaba County

The hills ranging far and wide across country were deep then in long-leaf yellow pine, that rich growth of early Cahaba County, which has since given place to heavy marches of blackjack, hickory and chestnut trees, and clambering muscadine.

The banks of Mahan’s Creek droop with live oaks, cedar, and sycamore, yellow jessamine, and wild honeysuckle, yellow and red. Springs, at least forty in number, feed its course all along its way. Little wonder that it was so favored a place of the Indians. And here was the neighborhood of some of the earliest mills and forges of Alabama.

Mahan family

The foundations of the industry in these counties of Bibb and Shelby were thus laid as far back as 1815 by the Mahan boys. They were sons of old Major John Mahan, an officer of a Maryland regiment in action in the Revolution. Always a fighting clan, Irish to the core, they carried a gay spirit, like flag and drum, into the smoky hills and rough pioneer times of early Alabama.

The old major emigrated to Tennessee at the close of the eighteenth century with his wife (who was close kin to General Winfield Scott) and their four boys. The blacksmith and wagon making business being at that period lucrative and useful in the growing communities, all four of the sons were bred to it.

At the first chance for a fight under Andy Jackson, however, they quit for the time being. When they settled at length in the Alabama country, the old major came down with them. He died a few years later at a good old age. His grave is in the old hill cemetery on what is Joseph R. Smith’s farm today, (1901) the precise site of the old Indian village and the early Mahan settlement. Major Mahan’s name is recorded there on the lichened gravestone, and 1820, the year of his death.

Lived in wigwams and log houses

The group of pioneers with their families lived first in wigwams, then later built log houses. All over this section of Bibb County are these log houses built in old Tennessee style and long abandoned.

The Mahan boys and the others started mills, limekilns, road building, farming, and wagon making. They sold wagons to the Government and contracted to help move out the Indians. In the long western procession of the tribes that so soon followed, the Mahan make of wagons led the van.

Mrs. Mahan relates how Edward Mahan, her father-in-law, used to tell about seeing “whole rooms packed with beads” which the Federal Government Agents gave to the Indians for their lands instead of the money they were authorized by the administration to give in square deal. The Mahans also did considerable railroad construction work and trestle building through south Alabama.

Brierfield Grist Mill on Mahan Creek, photo taken ca. 1890 (Alabama Department of Archives and History)

Politics

Jesse Mahan, a son of Edward Mahan, became in after years something of a figure in the political affairs of this section. He was also a Union man. When pressed at length into the service of the Confederate Government, he took his slaves and conducted the salt works near Mobile. Later made iron inspector by the Confederate Government with the rank and pay of major, he had also charge of the timber and wagon department, shipped timber to Selma from his sawmill on Mahan’s Creek, and donated several acres of his property on the Creek for the Confederate rolling mill at Brierfield.

He served as a member of the Constitutional Convention during the reconstruction times, and as State senator from Bibb in 1868. His father and uncles built the first flat and keel boats ever floated on Cahaba River to carry coal. They surveyed the county lines and removed the county seat from Randolph to Centreville.

SOURCE

Excerpt from The story of coal and iron in Alabama by Ethel Armes, Pub. under auspices of the Chamber of Commerce, 1910