Indian Trails and Early Roads written in 1900

by

Peter J. Hamilton

Scroll down to read story

(Unedited Transcription from Publications of the Alabama Historical Society, Miscellaneous.. Volume 1 by Alabama Historical Society)

Roads made Roman history, and with the development of roads everywhere comes the evolution of a country. A wagon road in the settlement of Alabama counted for more than a nickle plate railway does at the present time, because the railway is simply an improvement while the wagon road was the essential beginning. Back of them were the Indian trails, which we are now to consider.

Peter Joseph Hamilton (findagrave.com)

INDIAN TRAILS.

The Chickasaws and Choctaws were generally hostile and no regular roads were to be found between them. The Cherokees were not sufficiently identified with the Gulf history to leave much trace in our section. But the Choctaws seem to have had a path which crossed the Bigbee at or near McGrew’s Shoals, ran thence along the Alabama, and about Cahaba crossed this river to the Upper Creeks, while the Creeks themselves had quite a system of roads. The routes of the Spanish explorers followed these lines also.

Roughly, we may say the Creeks extended from somewhat east of the Tombigbee eastwardly to the Ocmulgee or Oconee. So we might expect that there would be a trail from the east Georgia region northwestwardly to the Cherokees, another towards the famous towns of Cosa, or Coosa, commanding the Upper Coosa River, “an old beloved town” or city of refuge, and a third westwardly to Coweta on the Chattahooche and the capital Tookabatcha on the Tallapoosa. The trails we would expect to concentrate in what is now east Georgia and pass eastwardly to the Atlantic coast tribes. The lower Creeks again might be expected to have a route of their own to St. Mary’s River and the coast.

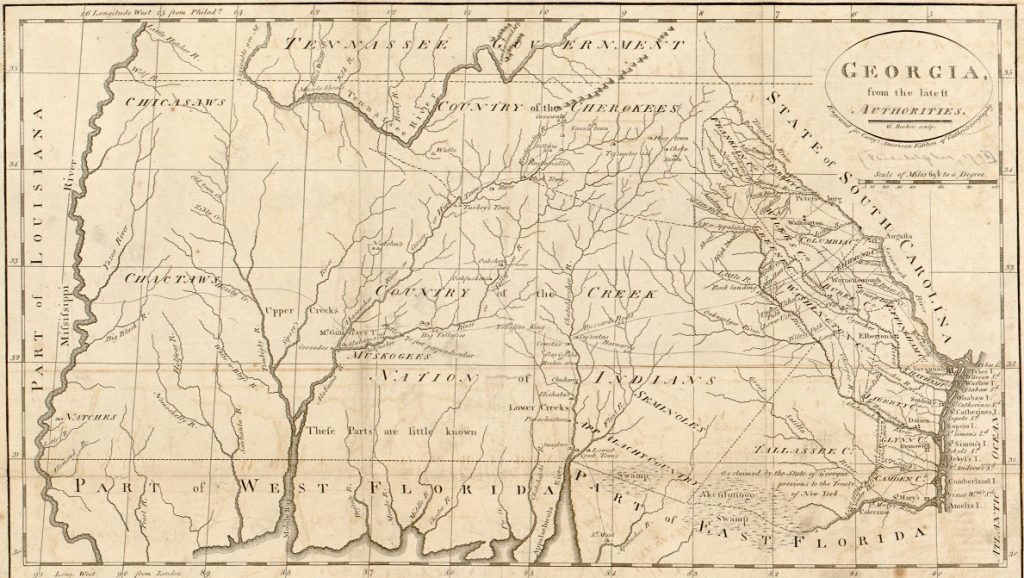

1795 map of Georgia and Alabama showing Indian territory

And these seem to have been the actual routes. The first was called the High Town Path, and started from High Shoals on a branch of the Oconee, crossing the Chattahooche at Shallow Ford north of the present city of Atlanta, whence it went to High Town or Etowah, Turkey Town, and the other villages nearest the Cherokees, continuing ultimately to the Chickasaws. The second, or upper trail, crossed the same river considerably -further down. The third, or southern trail, came from Rock Landing on the Oconee, (below our Milledgeville), and proceeded westwardly, crossing the Chattahooche in canoes about Cusseta and Coweta, (be1ow Columbus). After reaching Tookabatcha, it turned north on the west side of the Coosa River to Coosa Town. On or near this route were subsequently established Ft.-Hawkins, Macon and the Flint River Creek agency in Georgia, and it was varied afterwards on the Alabama side to connect both with the British at Okfuskee and the French at Ft. Toulouse, below our Wctumpka. The fourth route (that from the Lower Creeks) fell into disuse as the whites appropriated the Atlantic coast of Georgia.

The Creek trails to the southwest were less numerous, but we know there was one south of the Alabama River, which, as above noted, branched across that river to the west to reach the Choctaws, while another branch continued southwestwardly towards the Mobile and Pensacola country, pursuing ridge routes where possible.

TRADE ROUTES.

French trade from Mobile was principally by the river, but there was a land route to Fort Toulouse, which doubtless joined the one from Pensacola, running through thick forests south of the Alabama to the same place, and in Bartram’s time the great trading path for West Florida. This was at a distance from the river and to some extent a ridge road. On it was Dead Man’s Creek, so named from the corpse of a white man found murdered. West of the Tombigbee and Mobile Rivers the three divisions of the Choctaws lived and traded largely to Mobile by a good road running not far from the river about the St. Stephens region. Thence it went westwardly via the village Youane (near modern Shubuta) through the Nation to the Mississippi. In English times a lower branch ran almost directly from Mobile to Youane, and the neighboring village of Chickasahay. Bartram in 1778 found no real “highways” between the Ocmulgee and Mobile, but that from Mobile to the Choctaws became permanent enough to be the boundary of three American counties. In 1809 Wayne was created west of it, between the Choctaw boundary and the Spanish line of 31°, and Baldwin was constituted out of so much of Washington County as lay-east of the trading road and south of the fifth township line. The road left Mobile at a ford on Bayou Chateaugué, (or Three Mile Creek), which was apparently called the Portage, long known as near the northwest corner of the American City, and its course in the present limits was somewhat that of Spring Hill Avenue.

The portage system cut less figure in our section than where the head waters of the Mississippi River interlock with those of the great lakes, less even than between the bayous of the lower Mississippi. There was one at Pascagoula, and another used by Spanish traders from Mobile, over the three miles separating the source of the Tombigbee from a tributary of the Tennessee. But the country was rougher and the trade less than in the other quarters.

The traders generally went in companies of fifteen to twenty men, with-perhaps seventy to eighty pack and other horses. The horses were permitted to graze at night and the start in the morning was after the sun was high. The loaded animals fell into single file, and were urged on with whip and whoop at a lively pace.

COLONIAL ROADS.

The French made few roads, except within their own settlements. To reach the Indians they used the rivers and the old Indian trails. A military way was projected by the British from Mobile to Natchez, which would have been of value in the control of the West by the Mississippi River, and in preventing the dispatch of supplies by the Spaniards to the Kentuckians and other rebels; but nothing actually came of it. The only road certainly opened was one from Mobile to Pensacola, the capital, at the instance and largely at the expense of the Mobile merchants. The object was to receive sooner their English mail and freight. This was by ferry over the Bay to the village near Bay Minette, and thence by land to Pensacola, with a short ferry over the upper Perdido River. The government assisted in maintaining this route. It would be interesting to know more of this post road and of the postal connections with Europe; but little is available. We do know that English traders were everywhere, and Bartram mentions meeting emigrants for the banks of the lower Alabama.

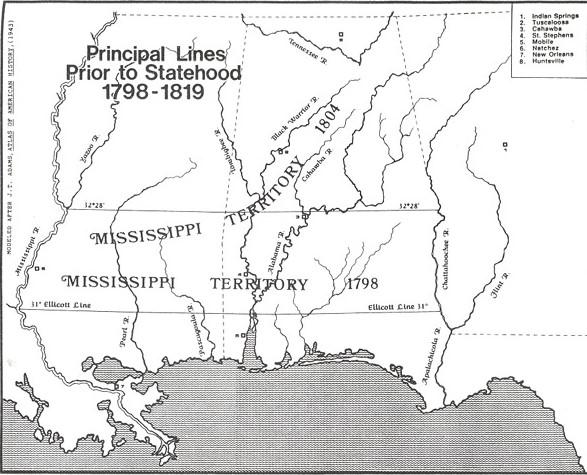

Georgia and Alabama map 1828 (www.libs.uga.edu)

AMERICAN HIGHWAYS.

In course of time after the Revolution, various roads connected the Atlantic States with the country west of the Alleghanies, and are to be thought of as superseding or at least supplementing the river routes. But Natchez and St. Stephens, making up the best part of Mississippi Territory, long remained isolated advance guards of civilization. Natchez communicated with the world by the Mississippi River, while the Tombigbee settlement was separated by the Choctaws from the Mississippi, by the Creeks from Georgia, by the Cherokees and their mountains from Tennessee, and by the Spaniards from the Gulf.

The United States made peace with these Southern Indians at the close of the Revolution, defining their boundaries, and in 1801 Brigadier General James Wilkinson, Benjamin Hawkins of North Carolina, and Andrew Pickens of South Carolina, as United States commissioners, concluded further treaties with the Chickasaws and Choctaws providing for a. wagon road from the Nashville country to the Natchez district, crossing the Tennessee River at Muscle Shoals. This was also the line of an old trail.

The road was duly laid out and its importance to the Southwest, and especially to Mississippi, can hardly be overestimated. It brought a population and civilization which not only filled up the old bounds but gradually overflowed them and finally led to the removal of the Southern Indians west of the great river.

On this road was Doak’s Stand, famous in treaty annals. On it also the cultivated Silas Dinsmore as agent long cared for Choctaw interests, once defying Andrew Jackson; and at the Muscle Shoals ferry lived the Chickasaw Colberts, for whom a county has been named. South of the Tennessee it was in general a ridge road between the Big Black River and the rivers flowing to the Gulf.

If immigrants should wish to travel by land from Columbus, Georgia, to Mobile River in those days before railroads and towns, they would pursue a different route. They would naturally go west to a point shortly below the junction of the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers, so as to keep in touch with the country drained by these, and thence southwest, following the water shed between the streams flowing into the Alabama and those emptying into the Gulf. And if one should take up a good map of our State, like Dr. E. A. Smith’s, and run a finger along this route, he will find on or near it Fort Mitchell, Fort Bainbridge, Fort Hull, Mount Meigs, Fort Deposit, Burnt Corn, and Fort Montgomery.

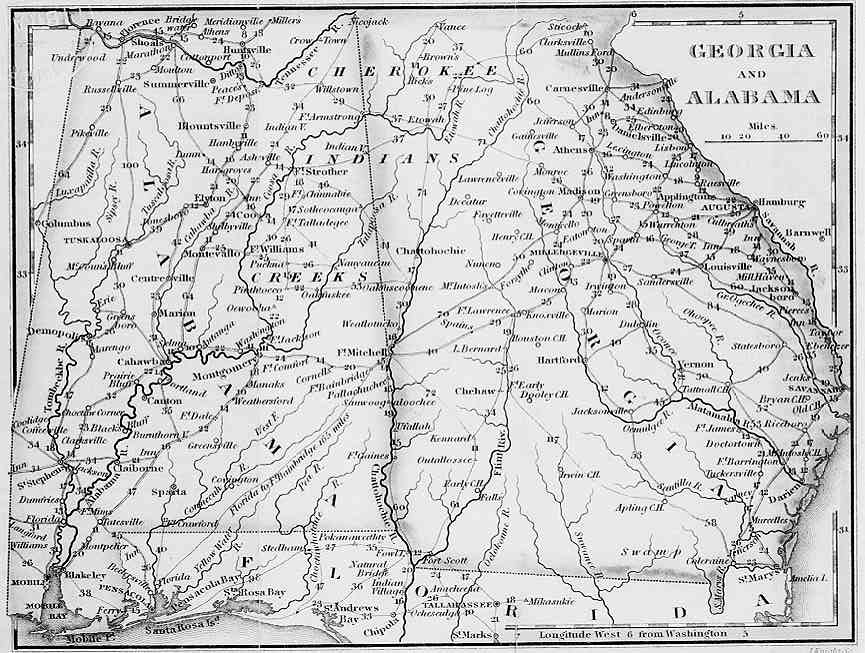

1812 map showing locations of Forts

He would in a manner be pursuing the old Federal Road, opened by the United States authorities from the Ocmulgee River in Georgia to Mims’ Ferry for St. Stephens in Mississippi Territory, along the route of the Southern and Southwestern Creek trails. This was done under article II of the convention at Washington of November 14, 1805, made by Henry Dearborn, Secretary of War, as United States commissioner, with William McIntosh and other chiefs.

Two years later Harry Toulmin, James Caller and Lemuel Henry as territorial commissioners extended it westwardly from St. Stephens to the capital at Natchez, opening also a ferry across the Alabama above Little River and across the Tombigbee above Fort St. Stephen. There was an older and more used ferry at Nannahubba Island lower down, dating from 1797. A road across ran from Mims’ Ferry on the Alabama River to Hollinger’s over the Tombigbee, but it was one continuous ferry, at high water. Cofl’ee’s army is said to have used this lower route in marching from west of the Bigbee to Benton’s new fort at Montgomery Hill on the way to Jackson’s capture of Pensacola.

Causeways were laid over “boggy guts and branches” of the new roads and its alternate name of “Three Chopped Way” came from the triple blaze marking it from Natchez to Georgia. While it was a bridle path, it was used principally for horseman and packhorses, but one of the oddest vehicles brought by immigrants was the rolling hogshead. Goods were packed in a hogshead, trunions or the equivalent put in the ends, and to them were attached shafts. We may suppose horses were generally hitched to this novel affair, but in one instance at least it was an ox, and in this manner the Coates family in 1800 and others later moved to Clarke and other southern counties. By 1812 Josiah Blakeley writes that it had become a wagon road and also ran to Baton Rouge, although even as late as 1817 the Greggs had to widen the way at some places for their wagons. This rough highway, at first not more than a blazed path, played for Alabamathe part which the stone Via Appia did for the country south of Rome. But for the Federal Road, with its forts, there had been no Alabama as we know it. The road itself can now be traced only with difliculty, but it is the east ‘boundary of Monroe County, and the original north line of Mobile County seems to have been the Fort Stoddert Baton Rouge extension.

There were other highways in course of time, such as Jackson’s military road, cut southwardly from the Tennessee River, which was serviceable in subjugating the Creeks, and the “great Tennessee road” to Jones’ Valley, and another cut via the High Town trail and Attalla from the east. There were others in South-East Alabama in the first Seminole war, and the different Indian cessions also necessitated corresponding highways. But these were chiefly developments, and not of the same creative importance as the Federal and Natchez routes.

Lorenzo Dow diaries

An instance of the difference between travelling before and after the Federal Road was cut may be found in the life of the eccentric but earnest Methodist preacher Lorenzo Dow. In 1803 he was in Georgia and set out for Tombigbee, by way of the agency of Hawkins, who “treated them cool.” In thirteen and a half days after leaving the Georgia settlements they reached the first house in the Tensaw district. His only notice of the “road or rather Indian path” was that they lost it once and then it took a good woodsman to find it again. He preached at Tensaw on a Sunday, and kept also a string of appointments across the swamp and the rivers. This was at a thick settlement, which must have been about McIntosh Bluff, and a scattered one above, seventy miles long. It then took him six and a half days to reach the Natchez settlement. At the end of December, 1804, he returned, but the only road he mentions is the trading road from the Chickasaws to Mobile, near Dinsmore’s agency and Fort St. Stephen. At St. Stephens he found but one family. He seems to have tarried six days in the Tensaw settlement, holding meetings, and in early January traveled on to Georgia. In the Creek nation there were so many by-paths as to make it difficult to find their way. Charges for entertainment were high. On the first trip near Tensaw he paid $1.50 for a night’s lodging, and now at Hawkins’ eleven shillings, “although not worth the half.”

Lorenzo Dow (Library of Congress)

Later Peggy Dow recounts a similar trip east by way of the Bigbee settlement in December, but does not give the year. It was Lorenzo’s tenth passage, however, to and from Natchez. There seems to have been an Indian path, crossing a slough called a “Hell Hole,” and they went over a river by night. They staid two or three days in the St. Stephens neighborhood, and she notes the Tombigbce there as beautiful, with water clear as crystal. St. Stephens was small but made a handsome appearance. They crossed by a ferry and in a day and a half passed over the Alabama too, a beautifulriver, “almost beyond description.” This was probably at or near what is now Claiborne. They then struck the road cut by order of the president from Georgia to Fort Stoddard (sic.) They frequently met people on it removing to the Tombigbee and other parts of Mississippi Territory. The road having been newly cutout, the fresh marked trees served for a guide; there was a moon but it was shut by clouds.

The troubles of immigrants on these routes can well be pictured from the journal of Rev. John Owen, describing the removal of his family in 1818 by wagon from near Norfolk, Virginia, to Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The roads in old settled Virginia he declares bad enough, but, after he passed through Beauford’s Gap of the Alleghanies and descended the Holston Valley via Knoxville, sickness, upsets, breakages and discouragements were their daily experience. Even before he reached East Tennessee he wished that he had not been born. Between “infernal roads” and straying horses, he declared “the Devil turned loose” in good earnest. He seems to have gone down the Sequatchee Valley to the Tennessee River. Exactly where he crossed into Alabama Territory in the Cherokee boundaries does not appear, and the only definite point named in the eight days between there and his destination is Jones’ Valley, near modern Birmingham. Possibly he crossed at Nickajack and from the Georgia road went down Wills’ Valley, along the route of the present Alabama Great Southern Railroad.

In Alabama he found the smiths lazy, meal scarce, corn and fodder high, and people rough and “shuffling,” but he does make one of his few entries of “roads good,” and he does not mention as many accidents at this end of his route as before crossing our line. May be he had become used to them. The day after Christmas he makes the entry, “past broken roads and got to Tuscaloosa and feel thankful to kind Heaven that after nine weeks’ traveling and exposed to every danger that we arrived safe and in good health.”

It would be a mistake, however, to think of these early roads as used only by the military and by immigrants. The general government employed them for post routes also. The early Mobile newspapers, and the corporation minutes before them, have a good deal to say about the mails. Human nature being much the same as now, we are not surprised to learn that it was often in the way of complaint. In February, 1816, the town commissioners addressed an official “monstrance” to Postmaster General R. J. Meigs, stating, that, despite good roads and weather, the failures of the contractor of the Georgia (Federal Road) route were beyond all precedent, and that merchants had to make private arrangements for communication with Fort Stoddard and St. Stephens, as there had been but two mails received thence since the first of the year.

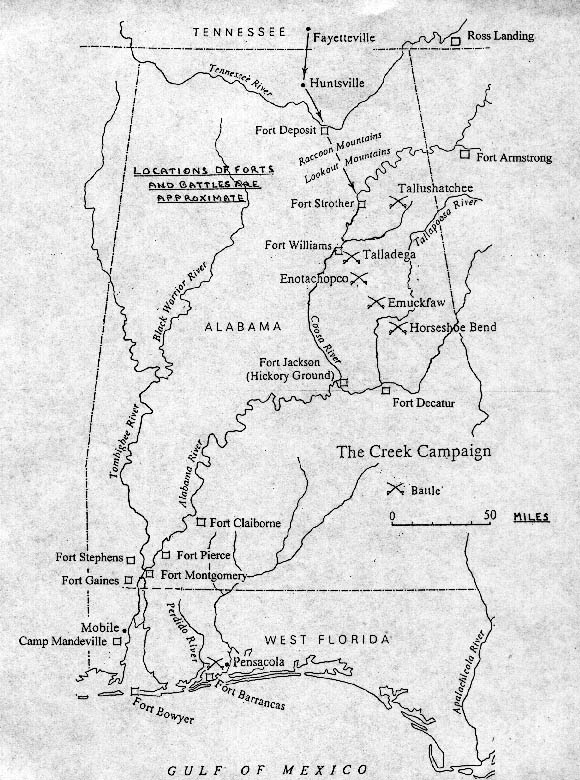

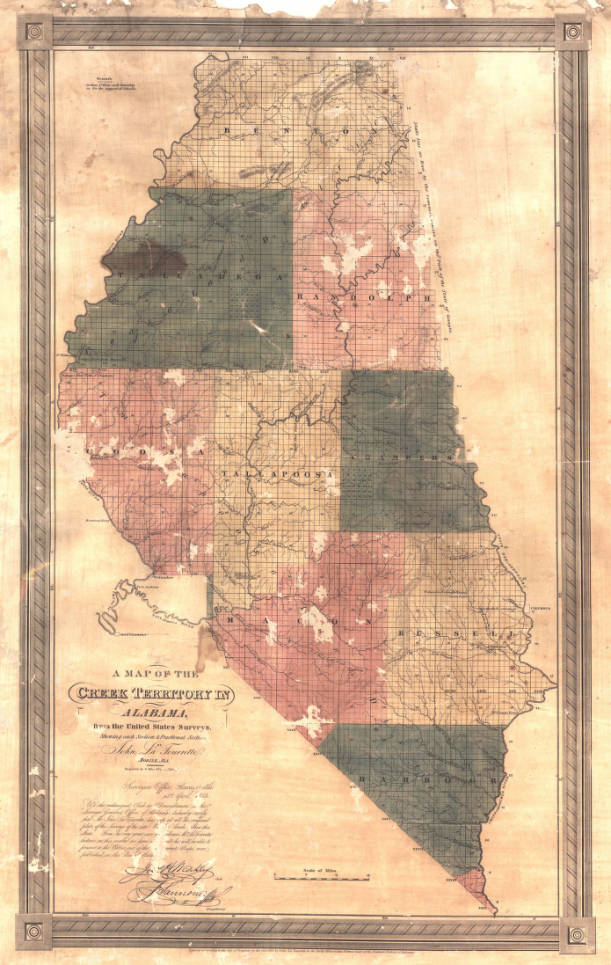

1833 Creek Indian territory John LaTourrette(Alabama Department of Archives and History)

Between then and LaTourrette’s beautiful map of 1835 the country had greatly developed, but several main roads of the older time could be distinguished from the network of highways about Tuscaloosa, Cahawba and other growing towns. There was still the thoroughfare up Wills’ Valley, continuing over the divide southwardly through the Cahawba Valley to the cotton lands of the Alabama River. About the divide it connected across the mountains by means of the old routes from Georgia with the Jonesboro road to Tuscaloosa traveled by Owen, and about Elyton came in the well known Stout’s Road from Somerville and the Tennessee Valley. Another north and south road was Cheatham’s, from Moulton to Tuscaloosa, then the capital, and somewhat further west Byler’s Road ran by way of Northport from Tuscaloosa to Florence. But with this map we reach modern ground; for on it we find the railroad from Decatur to Tuscumbia, and also the one from West Point to Montgomery.

The aboriginal trails were the paths of white explorers, from Spanish discoverers and French coureurs dc bois to the American pioneers like Boone and Dale, and, between these extremes, competing British and French merchants carried their wares over the same routes to reach the native tribes. The colonial governments in building roads also followed some of the trails, and the later American military and territorial authorities with their more important highways kept the same general course. Even our railroads sometimes pursue them, because they offer the least natural obstacles, although the growth of cities has made railways sometimes seek directions unknown to earlier roads. But as the trails, trade routes and early roads sought the ridges, the directions of all are analogous and sometimes identical, and they constitute but one historical development.

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Exploration: A Collection of Lost & Forgotten Stories

Alabama Footprints – Exploration – is a collection of lost and forgotten stories about the people who discovered and initially settled in Alabama.

Stories include:

First Mardi Gras in America

The Mississippi Bubble Burst

Royalists settle in Alabama

Sophia McGillivray- A Remarkable Woman

The Federal Road – Alabama’s First Interstate

I will gladly become a patron if you will tell me where to mail the money. I do not conduct financial transactions using my iPhone.

I’m sorry Agnes. The Patreon Program only works online.

do you know if this story has any information on the trail leading west from Pensacola requiring a ferry or canoe passage across Perdido Bay (near Lillian) then leading from there to “the village” near Daphne?

This trail is often confused with the later “old spanish trail” which leads north out of Pensacola crossing the perdido river near the present day highway 90 bridge.