(Continued)

Events in the life of Joe Gillespie born 1853 as told by him in 1939 – Part III

SCROLL DOWN TO READ STORY

(Transcribed WPA Life story)

JOE GILLESPIE

Belmont, Alabama

by

WPA writer

Ruby Pickens Tartt

written Jan 17, 1939

“One of the most hellish crimes was back in ’52 (1852) when a Negro named Jack Turner living in Choctaw tried to exterminate the whites. He had formed a club of 400 members and had a mature and well organized plot to kill all the white people in this section. But the papers with all their plans were found near one of their hideouts. In these papers they stated they had 400 Negroes ready with powder shot and guns; that they thought themselves sufficiently strong to accomplish their designs, and that Sunday night the 17th of September had been appointed as the date. The papers showed that this date had been selected because the people would be at a camp meeting unarmed and could then offer no resistance. The papers were taken before the solicitor and a quiet meeting of all the citizens of the town was held to discuss the best way to suppress the outbreak and massacre. It was decided that six of the ring leaders who had been assigned to the duties of leading squads to all the towns to kill the whites should be arrested and put in jail. This was done, without bloodshed as the Negroes suspected nothing. Then the whites held a mass meeting on the same day. This brought about eight hundred men and among them 150 Negroes. The papers were read, the names given and by almost unanimous vote they decided Jack Turner, the leader, was a dangerous Negro, a regular firebrand in the community; and they demanded his death. He was hung in the presence of the large crowd and his death put an end to any further trouble there.”

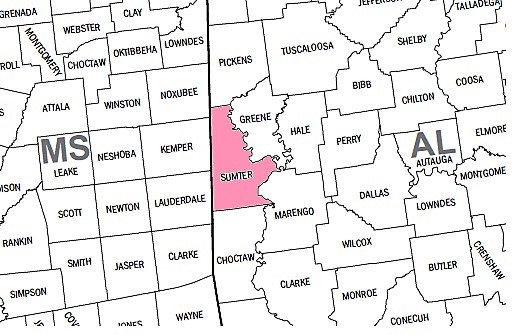

“Renfroe had nothing to do with that. He was at Livingston doing everything he had no business doing. Indicted for conversion of money, embezzlement, grand-larceny, burglary, assault with intent to murder, murder, he was sent to Pratt Mines for five years but in less than sixty days he had escaped and was hiding in the flat woods near Livingston, a belt of uninhabited timber land 90 miles by 15 miles wide. No one dared try to arrest him there. The last mule he stole was from his brother-in-law, Sledge, and the silver found on him when he was finally captured belonged to Mrs. Harris, one of his closest friends who had befriended him many times. They could not keep him in jail. He burned a hole in the floor of the jail under a bathtub and escaped from Tuscaloosa and while in the Livingston jail he wrote a note to a friend, asking for muriatic acid and a ball of yarn, but the note was intercepted. He finally escaped and was captured in 1886 at Enterprise, Mississippi, brought back to Livingston and put in jail. McCormick was sheriff at the time. Renfroe asked for a drink of whiskey as he got off the train and he got it. What a strange contradictory career this was.”

“Nursed in the lap of luxury, a young soldier, a tiller of the soil, a hero brave almost to rashness, he broke the neck of more than one negro insurrectionist and contributed more than any other tot he restoration of peace and safety in Sumter County. But Sumter had endured all it could from Renfroe and so about 8 o’clock one night he was brought back. While McCormick was at the telegraph office making inquiries of State authorities at Montgomery as to what to do with him, a mob of armed men broke into the jail, overpowered the jailor and, having found the keys to his cell, took him out and hanged him to a tree near the Sucarnatchee. Pinned to his back was this placard, ‘The fate of a horse thief.’ This ended the career of the most desperate character Sumter County ever produced.”

At this point Mr. Gillespie sighed, which I first though was an expression of sadness over the Renfroe blight on Sumter’s history; but with the sigh, he slumped perceptibly and I remembered that he was an old man and easily tired. I immediately departed, but not before promising to return for another visit.

Alabama’s Outlaw Sheriff, Stephen S. Renfroe (Library Alabama Classics)

“This vignette of local southern history . . . recounts Renfroe’s career as sheriff of Sumter County for a little more than two years, followed by six years of bizarre activities as a fugitive from justice before being lynched in July 1886. . . . He led the local Ku Klux Klan in 1868-69, participated in the Meridian riot of 1871, and took part in the killing of two active Republicans, one white and one black, in 1874. Rumors attributed other slayings to this violence-prone man who in 1867 had fled another county after killing his brother-in-law. . . . The story clearly illustrates the violent tactics of the redemption process.”—Journal of American History