This story is an excerpt from the book ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Settlement: Lost & Forgotten Stories (Volume 2) continued below

Three countries, England, Spain & France, claimed parts of the newly explored land in American which included the future state of Alabama. Since the majority of land in Alabama was still occupied mainly by Native Americans, the three countries encouraged the Native Americans to join forces with them and drive the rival countries out. The alliances formed created division within the Native American population residing within the future state of Alabama.

Carolinas wanted a barrier against the Spaniards

The English Carolinas were desirous of interposing a barrier between themselves and the Spaniards of the Floridas on the one hand and the French of Louisiana on the other. To carry out this desire, James Oglethorpe proposed to establish a colony upon the western bank of the Savannah in Georgia.

In February 1733, Oglethorpe landed on that river with thirty families, numbering one hundred and twenty-five persons, and immediately laid out the city of Savannah. Calling the chiefs of the Lower Creek Nation together, he obtained from them a cession of all the lands between the Savannah and the Altamaha.

Augusta became a trade center

During the following year this colony was increased by a company of forty Jews; of three hundred and forty-one Germans, and by many Scots, who settled at Darien. Two years later the town of Augusta, Georgia was laid out, and a fort established there. Augusta became the scene of an active trade with the Indians. Over six hundred whites were engaged in this trade.

A highway was constructed between Augusta and Savannah, and boats plied between those towns and Charleston. After only five years from the landing of Oglethorpe, the colony of Georgia had received more than one thousand settlers from the trustees of the company, and several hundred more who came at their own expense.

Georgia claimed all the territory east of Mississippi

Georgia claimed all the territory from its eastern border to the Mississippi as belonging to her under the charter granted to Oglethorpe. As the colony filled with population, the tendency was to continually press westward. The Native Americans opposed it as trespassing upon them west of the Ocmulgee. The result was frequent clashing between the English settlers and the Native Americans. When war broke out between England and France, the Native Americans usually allied with the French.

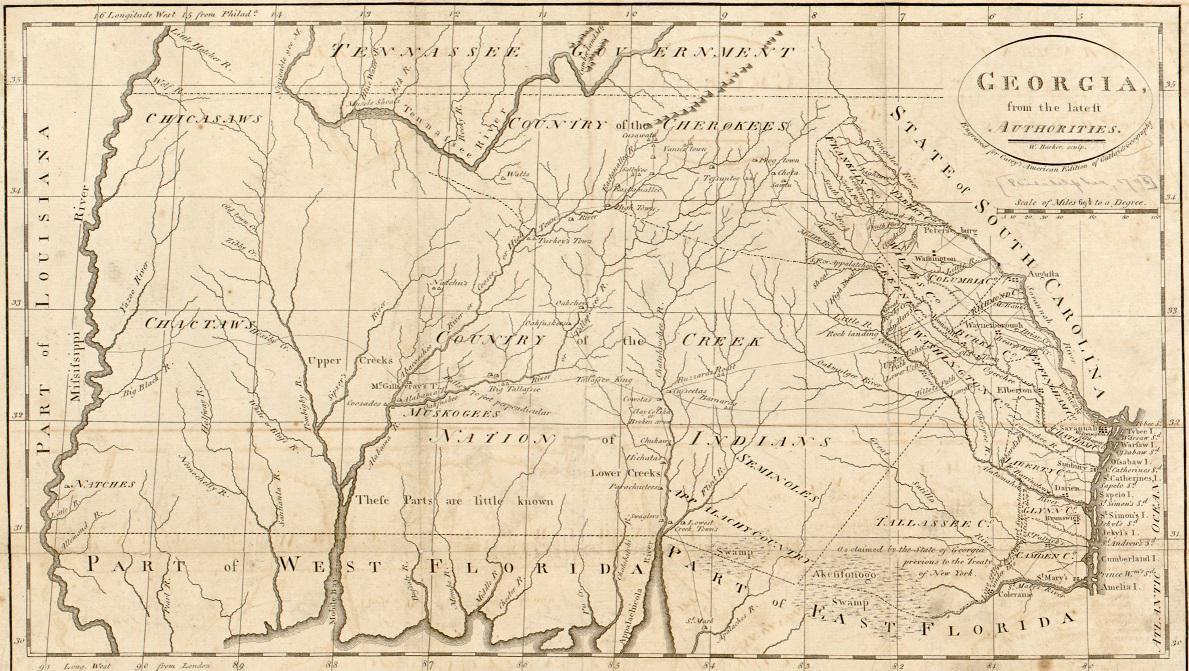

1795 map by William Barker (Library of Congress) shows Native American territory in the center and Mississippi River far left

1795 map by William Barker (Library of Congress) shows Native American territory in the center and Mississippi River far left

The rapid growth of Georgia alarmed the Spanish Government and led to a series of skirmishes between the English and Floridian Spaniards. Oglethorpe wisely formed alliance with the Lower Creeks. In their treaty it was stipulated that no one but the trustees of the colony of Georgia should settle the lands between the Savannah and the mountains.

Upper Creeks did not recognize cessions

The Upper Creeks being under French and Spanish influence did not unite in this treaty. They never recognized the cessions to Oglethorpe made by the Lower Creeks. Although the English held a garrison at Octuskee on the eastern bank of the Tallapoosa river within forty miles of Fort Toulouse which had been established by Bienville, they only succeeded in converting to their cause a few of the Upper Creeks.

By May 1736, Bienville was determined to destroy the last vestige of the Natchez tribe, who had fled from French arms upon the Mississippi, and who were now hospitably entertained by the Chickasaws in the hills of North Mississippi and North Alabama.

These Natchez refugees bore a deadly hatred for the French due to the destruction of their tribe, and lost no occasion to instill animosity against their conquerors in the breasts of the brave mountaineers. The English fanned the flame until the French were goaded by constant attacks upon their settlements to launch an expedition against the Natchez village which had been established in the heart of the Chickasaw nation.

Attack plan by French

It was planned that D’Artaquette should lead a force of French with their allies of the tribes of the Miamis and the Illinois from a point upon the Mississippi, and they should march eastward toward the heart of the Chickasaw tribe. At the same time, Bienville was to move up the Tombigbee from Mobile and march westward to the same point. The two forces would unite and extinguish the Natchez survivors and destroy English influence with the mountain tribes.

D’Artaquette reached the point of contemplated junction of forces but could hear nothing of Bienville. He determined to make the attack alone and reap all the glory. His force consisted of one hundred and thirty Frenchmen and three hundred and sixty Indians. He charged the Natchez town and found himself confronted by a body of thirty Englishmen and five hundred Chickasaws.

The Miamis and Illinois fled at once and the French were shot down by scores. Most of the officers were slain, and D’Artaquette himself fell into the hands of the enemy and was subsequently burned to death. However, a small remnant of the expedition escaped. The French guns and ammunition captured on the field were afterward turned against Bienville.

Bienville’s career ended

With an army of five hundred and fifty French and six hundred Choctaw allies, Bienville embarked at Mobile and ascended the Tombigbee to the head of navigation, now known as Cotton-Gin Port. Not hearing from D’Artaquette, he marched westward twenty-seven miles and encountered the first Chickasaw village.

The Cross, Bienville Square Park Mobile, Ala. ca. 1900 – Detroit Publishing Company

The Cross, Bienville Square Park Mobile, Ala. ca. 1900 – Detroit Publishing Company

To his astonishment he found it well fortified by stockades with loop-holes for musketry, and with the English flag flying over the fort. Bienville attacked the village and was most disgracefully driven back. His Choctaw allies gave him no assistance in the battle. He left his dead and wounded on the field of Pontotoc and hastily reached the river and descended to Mobile. This disastrous expedition terminated the official career of Bienville.

Read this story and more in ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Settlement: Lost & Forgotten Stories (Volume 2)

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Settlement: Lost & Forgotten Stories (Volume 2)

Very interesting I was always more interested in which Indian tribe was still around north Alabama prefer Marion county in the late 1800s as around 1890s. I can not find a reference to them. My grandmother users to talk to them in their language.

Really enjoyed this article! It takes me back to when I used to pick up arrowheads in my father’s fields. Sure wish I still had them! Would donate them back to the people whose ancestors made them!