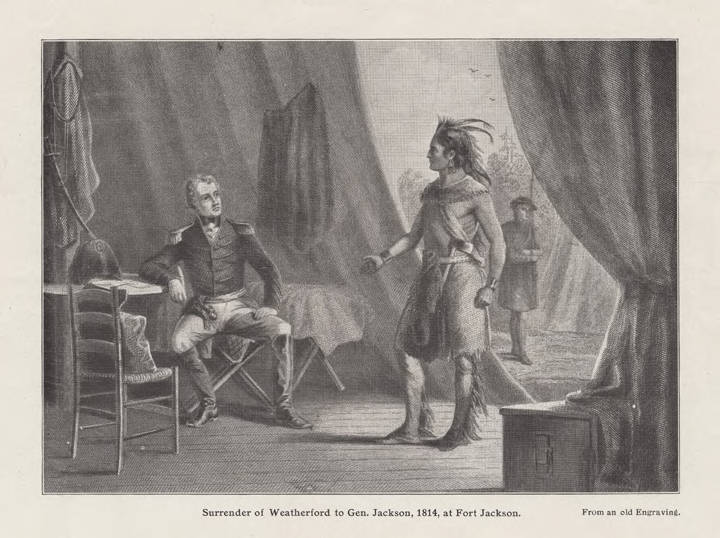

SURRENDER OF WEATHERFORD

By William Gates Orr,1 of Okolona, Miss.

(Transcription from Transactions of the Alabama Historical Society, Volume 2, 1898)

Okolona, Miss., Feby. 22, 1893.

Mr. H. S. Halbert,

Crawford, Miss.

My Dear Sir: March 5th, 1892, you wrote to me asking that I give you a statement of the facts of Weatherford’s surrender to General Jackson, as detailed to me by my grandfather. Business engagements prevented a compliance at the time and I plead guilty to subsequent neglect.

My grandfather’s name was William Gates. He enlisted at Pendleton, S. C. Was an orderly sergeant in Captain Williams’ Cavalry Company. As to Gates’ Regiment, Company and rank, you can get this from the Pension Office2 at Washington. His widow, who was his second wife, now draws a pension. Gates did a great deal of special scouting for Jackson and was about the General a great deal.

Mural by Roderick D. MacKenzie depicting the surrender of William Weatherford to Andrew Jackson

The morning of Weatherford’s surrender, he was near the General’s tent—say ten or fifteen steps. It was early. He saw Weatherford approach and ask a soldier where was General Jackson’s tent. Jackson came out. Weatherford walked directly and firmly to the General and asked, “Is this General Jackson?” The reply was, “Yes.” “I am Bill Weatherford.” Jackson extended his hand and taking Weatherford’s hand, said, “I am glad to see you, Mr. Weatherford.” My grandfather always emphasized the Mr., and commented upon the cordial and respectful manner of the General in receiving his foe. After the hand shaking, Weatherford, without parley, show or ostentation, said, “General Jackson, I come in to surrender.” Jackson’s reply was, “I am glad to hear it.” Weatherford said, “Our warriors are killed and scattered, our ammunition is out, our women and children are naked and starving. If we had warriors and something to eat, we would fight on.” Jackson said, “You are a brave man and I glory in your spunk.” They then walked into the General’s tent and my grandfather heard no more. Gates had read of the statements published of Weatherford’s surrender, and always ridiculed the idea of pomp or display. He said Weatherford was dressed in buckskin breeches. I do not remember as to his coat or headgear. Carried no arms, was afoot and alone, and my memory is very clear that he was not even escorted to the General’s tent by a guard. The general and vague impression that I have is that it was not customary for Jackson in that war and at that time to put out guards around his camp as was and is the custom when the war is between two civilized nations. Things were done loosely and no sentinels were thrown out unless they were close upon the Indians. There was order, of course, but more the order born of the honor and patriotism of the volunteers than military training. And the thing that impressed me most was the idea that the chief of the enemy without flag of truce, escort or parley just simply walked into the midst of Jackson’s army, asked for the General, told his business without ado, and left as he had come. After that, the same day, I think, perhaps later, the men, women, etc., came in and surrendered. Gates did not escort Weatherford to Jackson, or in any way have anything to do with it. He was merely a looker on. Your friend,

W. G. Orr

CRITICAL AND BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE.

By The Editor.

The Creek War may be called the Epic Period in the early history of Alabama, then a part of the Mississippi Territory. It has been the subject of numerous histories, memoirs, biographies, and some poetical composition. Tolerably full lists and references are to be found in Parton’s Life of Jackson, vol. i, pp. xiii-xxv; and Winsor’s Narrative and Critical History of America, vol. vii, pp. 435-6. Hardly a single work exists, however, in which there are not numerous errors, and not one covers the whole field. The very latest work—The Creek War of 1813 and 1814, by H. S. Halbert and T. H. Ball (Chicago, 1895. 8vo., pp. 331; ill.),—a valuable production, is not general, but deals with “that part which has not been as yet so fully given, connected with the white settlers in what is now South Alabama.” The real history of this struggle, with a critical study of its causes, its actors, the movement of events, considered both in its relation to a wider struggle and also in its local bearings, is yet to be written. When that is done there will be a consequent readjustment and a shifting of picturesque and heroic figures from exaggerated to real positions.

Of all incidents in the Creek War there is none that has been preserved with more dramatic detail than the surrender of Weatherford. The early narratives clothe it in romantic colors. The common sense view, however, is that it was only an ordinary affair, not differing in material respects from the numerous surrenders being made daily after the battle of the Horse Shoe. Eaton’s Life of Jackson (1818) contains perhaps the first and most glowing account, and the one mainly followed. The next authority in rank as an original is Pickett’s Alabama, vol. ii. pp. 347-351. Parton’s Jackson,vo\. i, pp. 527-537, contains a chapter on “The Surrender of Weatherford;” as does also Eggleston’s Red Eagle, pp. 329-339. Meek’s version is in his Romantic Passages in Southwestern History, pp. 283-287. Drake’s Indians (15th ed.) contains an account, pp. 390-91. Parton, Eggleston, Meek and Drake follow Eaton substantially, and each contains the concluding speech beginning: “I desire peace for no selfish reasons,” etc. Meek, p. 286, says that “as a specimen of oratory we know nothing finer than this address.” Pickett, p. 350, repudiates this part of the interview, and says that the statements “are doubtless based entirely upon camp gossip.” Parton, p. 533, admits that Eaton “may have added to the tale a slight presidential campaign flavor,” but says that he must have heard it many times from Jackson himself. Brewer’s Alabama, p. 437, note, speaks of Eaton’s story as “fictitious,” and follows Pickett. The latter is responsible for the deer-killing incident, of which Eaton makes no mention whatever, and which Woodward says has “been played off on the credulity of Col. Pickett.” Pickett, p. 348, says he rode the “grey steed” to camp that bore him over the bluff at the Holy Ground, while Meek. p. 280. says that this particular animal “sank to rise no more.”

Halbert and Ball’s Creek War, pp. 284-5, and Driesback’s “Weatherford” in the Ala. Historical Reporter, March and April, 1884. both late works, treat it as a plain and matter of fact occurrence. Mr. Driesback says he rode the “noble steed” that bore him through the war, but expressly makes the interview to consist of but a few sentences. Woodward’s Reminiscences (1859) is, however, the leading authority for the latter view, the author writing both from his own observations at the time, and from conversations with Weatherford. He repudiates the story of Weatherford’s noble self-renunciation as he soliloquizes whether or not he will surrender, as well as the deer incident, the elaborate dialogue with Jackson, and the pompous speech which usually concludes the interview. The surrender was made as a simple personal necessity; he walked into camp like numerous others who surrendered: and held an interview with Jackson in which they talked over the war. See Woodward’s Reminiscences, pp. 42, 43, 87, 89. 91-103.

1The writer of this letter, William Gates Orr, son of Judge John A. and Lizzie (Gates) Orr, is a lawyer of Okolona, Miss. His family is Scotch-Irish, and has been prominent in S. C. and Miss. His great-grandfather, John Orr (son of Robert Orr, emigrant) was in the Revolutionary War; and his grandfather, Christopher Orr (whose wife was Martha, daughter of Robert McCann, of County Down, Ireland) was a merchant and planter. His father is a lawyer of note and has been District Judge in Miss.; and his uncle, James L. Orr, was Speaker of the 38th Cong., Confederate States Senator, Governor of South Carolina, and died as Minister to Russia in 1873. For sketch, with ancestry, of Judge J. A. Orr see Goodspeed’s Memoirs of Mississippi (1891), vol. ii, p. 536540; and of Hon. James L. Orr, see Livingston’s Sketches of Eminent Americans, vol. IV, pp. 205-211, portrait, and Gov. B. F. Perry’s Reminiscences of Public Men (1883), pp. 179-188.

2The Bureau of Pensions, Washington, D. C, Dec. 1, 1898. furnished the following record: “Eliza, widow of William Gates, made an application for pension on April 14, 1879, at which time she was 50 years of age and residing in Chickasaw County, Miss., and her pension was allowed for the service of her husband as a sergeant in Capt. Kelly’s Company, South Carolina Militia, War of 1812, for a period of 182 days. He enlisted at Muddy Springs, South Carolina. Place and date of birth not stated.

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS – Volume I – IV: Four Volumes in One (Volume 1-4)

The first four Alabama Footprints books (listed below) have been combined into one book, Alabama Footprints – Volume I-IV –

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Exploration

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Settlement

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Pioneers

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Confrontation

From the time of the discovery of America restless, resolute, brave, and adventurous men and women crossed oceans and the wilderness in pursuit of their destiny. Many traveled to what would become the State of Alabama. They followed the Native American trails and their entrance into this area eventually pushed out the Native Americans. Over the years, many of their stories have been lost and/or forgotten. This book (four-books-in-one) reveals the stories published in volumes I-IV of the Alabama Footprints series.

I am a Patron and can’t access stories.