PIONEER TALLADEGA, ITS MINUTES AND MEMORIES

CHAPTER XI

INDIAN OCCUPANCY OF TALLADEGA

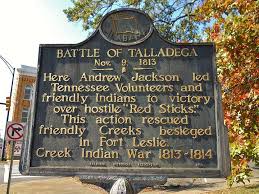

The battle of Talladega, fought between the hostile Creek Indians and eighteen hundred Tennessee soldiers under General Jackson at eight o’clock on the morning of Nov. 9, 1813, between the city spring and the iron furnace, at Talladega, lasted fifteen minutes.

Much fiction and guess work has been indulged in about this battle, the Historian Pickett embellishing it with the story of an Indian escaping from the beleaguered fort in a hogskin disguise, and bringing help from Jackson. Here is the account taken from Eaton’s History, from which source Pickett obtained much of his information:

“Late, however, on the evening of the 7th, (November) a runner arrived from Talladega, a fort of the friendly Indians, distant about thirty miles below, with the information that the enemy had, that morning, encamped before it in great numbers, and would certainly destroy it unless immediate assistance could be afforded. He (Jackson) now gave orders for taking up the line of march with 1,200 infantry and 800 cavalry, and mounted gun-men. By twelve o’clock that night everything was in readiness, and in an hour afterward that army commenced crossing the river about a mile above the camp. In this march Jackson used the utmost circumspection to prevent surprise, marching the army, as was his constant custom, in three columns, and by evening he had arrived within six miles of the enemy. Having judiciously encamped his men on an eligible piece of ground, he sent forward two of the friendly Indians and a white man who had for many years been detained as a captive in the nation, and was now acting as interpreter to reconnoitre the position of the enemy. About eleven o’clock at night they returned with the information that the savages were posted within a quarter of a mile of the fort and appeared to be in great force, but that they had not been able to approach near enough to ascertain either their numbers or precise location. By four o’clock in the morning the army was again in motion. The infantry proceeded in three columns, the cavalry in the same order, in the rear, with flankers on the wings. The advance consisted of a company of artillerists with muskets, two companies of riflemen, and one of spies, marched about 400 yards in front under the command of Colonel Carroll, the inspector general, with orders, after commencing the action, to fall back on the centre, so as to draw the enemy after them. At seven o’clock, having arrived within a mile of the position they occupied, the columns were displayed in order of battle. 250 of the cavalry under Lieutenant Colonel Dyer were placed in the rear of the centre as a corps de reserve. The remainder of the mounted troops were directed to advance on the night and left, and after encircling the enemy by uniting the fronts of their columns, and keeping their rear rested on the infantry to face and press toward the centre, so as to leave them no possibility of escape. The remaining part of the army was ordered to move up by heads of companies, General Hall’s brigade occupying the right, and General Robert’s the left.

“About eight o’clock, the advance, having arrived within eighty yards of the enemy, who were concealed in a thick shrubbery that covered the margin of a small rivulet, received a heavy fire, which they instantly returned with much spirit. Agreeable to their instructions, they fell back towards the centre, but not before they had dislodged the enemy from his position. The Indians, now screaming and yelling hideously, rushed forward in the direction of General Robert’s brigade, which, alarmed at their numbers, and yells, fled at the first fire. Jackson, to fill the chasm which was thus created, directed the regiment commanded by Colonel Bradley to be moved up, which, from some unaccountable cause, had failed to advance in a line with the others, and now occupied a position in rear of the centre. Bradley, however, to, whom this order was given by one of the staff, could not be prevailed on to execute it in time, alleging that he was determined to remain on the eminence which he then possessed until the enemy should approach and attack him, Owing to this failure in the volunteer regiment it became necessary to dismount the reserve, which with great firmness met the approach of the enemy, who were rapidly moving in this direction.

“The retreating militia, seeing their places supplied, rallied, and recovering their former position in the line, aided in checking the advance of the savages. The action now became general along the line, and in fifteen minutes the Indians were seen flying in every direction. On the left they were met and repulsed by the mounted riflemen, but on the right, owing to the half of Bradley’s regiment, which was intended to occupy the extreme right, and to the circumstance of Colonel Allcorn, who commanded one of the wings of the cavalry, having taken too large a circuit, a considerable space was left between the infantry and the cavalry through which numbers escaped.

The fight was maintained with great spirit and effect on both sides, as well before, as after the retreat commenced, nor did the savages escape the pursuit and slaughter until they reached the mountains, at the distance of three miles. In this battle the force of the enemy was 1,080, of whom two hundred and ninety-nine were left dead on the ground, and it is believed that many were killed in the fight who were not found when the estimate was made. Probably few escaped unhurt.

“Their loss on this occasion, as stated since by themselves, was not less than 600; that of the Americans was fifteen killed and eighty wounded, several of whom afterwards died. Jackson, after collecting his dead and wounded, advanced his army beyond the fort and encamped for the night. Having buried his dead with all due honor, and provided litters for the wounded, he reluctantly commenced his return march (to Ten Islands, Fort Strother) on the morning succeeding the battle.”— Eaton’s Life of Jackson, pp. 53-60.

One hundred and sixty friendly Indians had fled to this fort for protection.

The fort was the residence of an Indian, friendly to the Americans, surrounded by a stockade, and was situated on the summit of a knoll two hundred yards south of South street, and fifty yards west of the channel of the spring branch, on property owned, in 1909, by the Talladega Furnace Company. One hundred and sixty friendly Indians had fled to this fort for protection. It was the home of a half-breed whose name was Samuel Leslie, but the name is written Samuel Lashley by Pickett, who starts a chapter on the battle of Talladega with the assertion, “In Lashley’s fort in the Talladega town, many friendly Indians had taken refuge.”

In the second case of the County Court docket, Minutes 3, page 60, there is a suit of Che Hadjo, plaintiff, versus Fos Hatche Fixico, Inthlenus Hadjo, Obice Joholo, and Samuel Lashley. On other pages of the record his name is written “Lashley.” On Deed record, page 4, of volumne A, there is a deed of a number of Indians of Talladega, Red Ground, Salt Creek and Chocolocco Towns where “Talumly Lastly’ is the first signature-evidently an Indian’s pronunciation of Samuel Leslie or Laslie, which was written by the clerk as he heard it pronounced. The Leslie Fort was, for a long time, the residence of Joel Stone, and continued to be such until after the war.

Indians never went upon the war path in large numbers without being led by some leader renowned in war, and experienced in battle.

Jim Fife, a noted Indian who lived in Talladega for many years after the battle, was the “runner” who conveyed the news of the seige of the fort to Jackson at Ten Islands. Fife is buried at the Brick Store on Chocolocco creek, a locality well known to this day. He met Jackson at Talladega on Jan. 16th, 1814, just before the battles of Emuckfau, Enitachopco, and Calabee. He was then the captain, or leader, of an Indian company omposed partly of Cherokees and partly of Creeks, numbering 200 men, and he bravely fought at the battles above mentioned. For many years previous to the Civil War the present “Brick Store,” or Elston place, or Simmons Mill, as it is variously called, twelve miles north-east of the city of Talladega, was an important trading place, and was universally known as “Fife’s,” because the Indian of that name lived there, and was interred there.

Pickett’s history contains a map and plan of the Battle of Talladega, but it is not of much value, as he has the points of the compass wrong-the map showing a stream flowing northeast from the big spring. There is no stream in Talladega county flowing in that direction-all water flows to the southwest, or south, in this county. The early settlers stated that the bones of a few Indians were on the plateau where the Deaf and Dumb and Blind Institutes stand, and where Moorfield and Stoneington are located, but none were found elsewhere. The white soldiers were buried in the Isbell field, just south of iron furnace, east of the Mardisville and Talladega road about two hundred yards and west of the branch about seventy five yards, and were surrounded by an enclosure of rock and a temporary fence until about 1902, when the Daughters of the American Revolution disinterred them, and placed their bones under a monument in the City Cemetery.

It is not at all likely that the number of hostile Indians engaged in the battle is correctly stated-and it is equally doubtful that the number of dead Indians is correct. By closely reading the account it will be seen that the three spies sent out the night before the battle were unable to form any estimate as to the number of the enemy-the battle lasted but fifteen minutes; some of the white soldiers were in a blue funk, and ran like rabbits; the Indians were concealed; pursuit reached three miles; Jackson buried his dead, and returned early the next morning.

Now, when, and where, and by whom was the accurate account that the “Force of the enemy was one thousand and eighty,” obtained? Who counted the two hundred and ninety-nine left dead on the ground? And why does Eaton speak of an estimate, if the whites were so accurate as to the casualties? There were less than one thousand Indians present at the last and fatal battle of the Horse-Shoe, when the whole force of the Nation was concentrated there to make a final and desperate stand is it likely that this number would have massed at Talladega to capture a miserable little for with less than two hundred Indians in it, all of whom were literally scared into epileptic fits?

At the battles of Emuckfau and Enitachopco, fought seventy eight days afterwards, when the Indians had abundant time for concentration and preparation, there were less than 500 hostiles engaged in each action.

A significant feature of the Battle of Talladega is that no history, and no individual has ever mentioned the name of a leading Indian chief who led the forces, or was engaged in it. No dead chieftain was ever found-and yet, Chinobee, Jim Fife, Leslie, and others were well acquainted with every hostile Creek leader of the Nation, and each one of these named friendly Indians was at this battle. Indians never went upon the war path in large numbers without being led by some leader renowned in war, and experienced in battle.

How unfortunate that the brave natives of Alabama had no writers among them to give the true facts of their battles, or to record their achievements!

As to the six hundred admitted by the Indians themselves to have been killed at Talladega, it may be said that there wasn’t one Indian in a thousand in those days who could count a hundred in English, or Indian either, for that matter, and when asked as to numbers the Indian was just as likely to give one number as another, neither of them meaning much to him. The leaves of the trees, the stars of the sky, the sands of the sea shore was his only way of conveying any number of a few dozen. Again, if the white men knew so accurately how many Indians were killed, why did they take any account of an admission made by an Indian that 600 were killed? Who killed these 600? The most of Roberts’ Brigade ran at the first fire. Colonel Bradley’s regiment failed to move up to where any execution could be done. The cavalry under Allcorn made too wide a circuit to catch any of the Indians. How unfortunate that the brave natives of Alabama had no writers among them to give the true facts of their battles, or to record their achievements! It can be stated without fear of successful contradiction that in all the Indian wars in Alabama there was never a field in which the Indian was not greatly outnumbered, and overmatched with superior weapons. It can also be stated that the battle of Talladega was one of those useless effusions of blood where nothing decisive was reached, no good resulted, no principle was vindicated. Within Leslies fort not a man was harmed, not a gun was fired at the fort, not an attempt made to capture it. The hostile force was never located within one quarter of a mile of the fort, and there was no demonstration on the part-of the hostiles to indicate their intention of capturing it, and had they captured it there was not a particle of danger to be apprehended on the part of the women and children of the fort, most of whom were blood kin to the Indians outside, and who were not held responsible for the views of their fathers.

The romance and glamour connecting Talladega with a battle so famous was the cause, years afterward, of its selection as a county seat. The locality was called the “Battle Ground” long before it became a hamlet, or even a cross roads.

Leslie’s stockade, located on the side of the McIntosh trail, eventually grew to be a trading point—after a while a settler built a cabin near the Big Spring—people came from Jumper’s Spring, or Mardisville, five miles away to look at the old battle-ground, another cabin was placed by the side of the one at the Spring. People continued to come into the new territory, and in a little while the “oldsettler” who lived on the site of the battle ground had been told, and had furnished himself with a bountiful supply of stories, legends, and traditions about the celebrated Indian battle, which grew in size and swelled into fiction as the years wore on, and the old settler observed that the retailing of these yarns made him an object of especial interest.

The friendly Indian, himself, with his ignorance of numbers, his taciturnity, and his ignorance of the English language, gave credence to many of these whoppers without intending to do so. The hog skin story can be dismissed as a pretty myth—as also the story of pulling a dead Indian out of the mouth of the big spring. The yarn that Jackson planted his cannon at the Exchange Hotel, and shelled the Indians who had surrounded the fort; and that he tied the United States flag to a tree near the graves of the soldiers, in the Isbell field, where it waved during the fight—all these can be classed as pretty fictions.

The white man can find in the Indian occupancy of this country many more beautiful, useful and honorable subjects of discussion than the Battle of Talladega, and themes that will in a little while be lost in oblivion unless some record is made of them. Talladega has a marvelous history reaching back into a beautiful past and it is not at all necessary that this battle should be kept in the foreground as a Jewel in her crown.

SOURCE

Transcribed from – The Alabama Historical Quarterly, Vol. 16, No. 01, Spring Issue 1954

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Removal: Lost & Forgotten Stories (Volume 7)

includes the following stories

- Plan for Indian Removal Started With President Thomas Jefferson

- Intrigue and Murder After Treaty At Indian Springs

- President Adams And Governor In A Stand-off

- Gold Causes Expulsion Of The Cherokees

- Cherokee Chief Ross Became Homeless

Andrew Jackson ‘rescued’ native Americans ? Really ? To be forced onto reservations!

Ken Barrow yes he rescued friendly Creek Indians that were besieged in the fort with traders.

This was 1813 and still Creek Territory. The treaty changing that was not signed until December of 1832. This was 19 years before that and was during the War of 1812.

Typical divide and conquer strategy. Andrew Jackson not related to queen of England that’s a plus.

Ken Barrow, reckon what happened to those “friendly Creeks”, during the land grab/roundup preceding the Trail of Tears?

Approximately 500 Cherokees joined forces with Jackson. They’d been fighting the Creeks over territory for years. History is never black and white.

Ken Rainwater, exactly. Jackson was a scourge for the native Americans. He’s the reason Davy Crockett left congress. He saw thru Jackson.

Ken Barrow Andrew Jackson also adopted a Native American son

Ken Barrow Crockett fought under Jackson in the Creek War, but he never saw himself as an Indian fighter. They later became political rivals, Crockett taking the non-removal side. But I don’t think Jackson ran Crockett out of Congress. I think Washington ran Crockett off. Crockett was uneducated and rough. He was jeered and made fun of in Washington as being a backwards hick. (Much like we see with our current president??) Fascinating period of our history just the same. Something our history books only cover with a sentence or two. I’ve always believed if the Red Sticks had not attacked Ft. Mims, Alabama today would be a more blended society. Assimilation had alredy begun with white settlers taking native wives.

Ken Barrow you need to study history instead of memes and mularky.

Jimmy Terry memes ?

Ken Barrow Fight stupid wars against innocent women & children win stupid prizes.

His story history like history channel is lie after lie.

Until the Lion learns to write the hunter will ALWAYS be glorified.

Jeffrey Love Sounds like some leaders of today!! So sad!

Betsy Burkhalter yes I have 25 years now documented in the south TRYING to convince rebel flag wavers and native American that the government is corrupt I’m serious.

Anybody ever hear of Poarch Creek Indians in Alabama? They apparently were never “removed”. Anybody know why? (Careful, it’s a trick question … )

Alex R. Moore because they aren’t a real tribe.

$

He hunted Indians especially in Florida.

Yes, those Cherokee that joined Jackson done so believing they would be able to remain on their ancestral land. Jackson lied, as soon as the Creek’s were defeated he turned on the Cherokee , rounded them up and marched them to Oklahoma, Jackson was no hero.

Thomas A. Mann If they were “all” lied to and removed, how were there Cherokee landowners and yes, slaveholders, in Alabama in 1850? How was it an entire unit of Georgia Cherokees fought in the Civil War for the Confederacy?

Alex R. Moore , all I can say is don’t believe everything you were taught in school. It took a few years of research to get to the truth. If you’re willing to do the research you’ll learn a lot about what you were taught.

If you were in Ft Leslie at the time, yes, you were “rescued.”

My family are Mvskoke Creek tribal members and escaped removal.

Anybody know why there were no Shawnees in north Alabama by 1800? Answer: The Cherokees and Chickasaws fought and killed them over hunting grounds, and forced them out long before white men ever arrived.

Wow, come on ppl, the truth will set us free, & I don’t mean go out & take down statues, Oh & by the way that Indian child was adopted as a souvenir really!

Came here for angry leftist white guilt apologist comments. Was not disappointed.

The Choctaw Nation of Indians now knows how to write.

The falsehood of Alabama history is due for an overhaul.

Fraud has no statute of limitations.

Chief Darby Weaver

The Tribal Leader

Son of Darby Weaver

Son of Hiram Crockett

Son of David Crockett Jr

Son of David Crockett / Crockett Weaver / D.C.

Son of David Weaver

Son of the The One Weaver

Darby Weaver I think this was the Creek Indians in this battle

I read the history as written in the Life of Jackson.

I also read the actual official version from the American State Papers which differs in context and details whereby Andrew Jackson is amiss to find any Indians to find contest with. His frustrations were apparent as was his blame pointed.

He did build roads apparently.

Seems like the official records state that Indians did not merely wait around to be slaughtered but would actually not be home when their would-be killers dropped by.

Needless to say eve American State Papers serve as Federal Statute whereas the versions accepted by Alabama history are not Federal Statute At Large.

Having battles in Court, I’ve learned that even Alabama Courts tend to have issue accepting the “History of Alabama”.

So… I no longer use it.

It lacks currency. If Alabama Courts cannot rely on Alabama Historians, that is very telling.

Chief Darby Weaver

After about $500,000.00 or so of my personal investment into learning whatever is available, I’m relying upon the documents that appear to be the actual documents of the day.

Reference: Worchester v Georgia (1832)

Reference: 1833 – Mushulatubbee calls for the removal of the settlers.

Reference: The Non-Intercourse Act of 1834.

Reference: 1835 – Land Patents declared fraud by Congress.

Reference: 1836 Petitions by Alabama Settlers to not be removed from Alabama at least till their crops came in.

Reference: The Act of March 3, 1837.

Reference: 1844-1845 – JF Claiborne explaining to Congress exactly what constitutes a Fraud.

Reference: 1844-1845 – Andrew Jackson confirming to William Crawford and JF Claiborne that he never sold a foot of Choctaw Land, any such pretense being the blackest of Frauds.

Chief Darby Weaver

The Tribal Leader

Therefore the land to the East of the Tombigbee that was the subject of the Treaty of 1820 and the CHOCTAW LAND in Alabama east of the Tombigbee which was patented by named sections is fully documented.

To be fair it is “East of the Mississippi River”.

It’s just not in Mississippi as is what is relieved upon today.

Those same settlers in 1836 had ancestors who also knew they arrived in the wrong location in 1810 after they arrived in 1807 and began to settle.

This also is a matter of Federal Record.

The Florida Campaign was interesting.

The Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 by General Wayne and the Choctaws and Chickasaws of Fort Stoddard Alabama is an interesting event that sounds like the same Battle of Fallen Timbers of the Creek War…

It’s interesting because those Chickasaws from the Choctaw Towns on 96 from Fort Stoddard are assisted by the Kunsha to deal with matters during this time.

Yes – Some are also called Miami (Mims) or Cherokee in 1791-1796.

There’s more to what I say. A lot more.

When taken as a whole history has a problem because none of what I am saying is known to the common person or history buff.

Yet – It exists and the Federal Records document what I am saying, more or less.

Otherwise none of my thousands of references should even exist otherwise.

Chief Darby Weaver

The Tribal Leader

Darby Weaver He found the Red Sticks en mass at Horseshoe Bend. This battle was well documented. Even the Red Stick leader, William Weatherford, was not full Creek blood. He was half-white.

Darby Weaver Interesting, but a serious question for you. With four generations of white grandfathers, how do you claim Choctaw status? (We all probably have SOME Indian blood in us, but there are very specific guidelines for claiming Indian status today.)

William Weatherford was described by Andrew Jackson as of the Hickory Tribe.

I grew up here and yes, for this particular battle, this is what happened in 1813. The round up was in the 1830’s. Y’all are condensing the timeline to a single point which distorts the perspective of the event but not the final outcome.