(Excerpt from ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Removal: Lost & Forgotten Stories (Volume 7)

Prior to 1830, it was the general consensus in the United States Congress that the Native-Americans should not be forced to voluntarily move from their homeland. But with pressure mounting from white settlers to acquire Indian Land, Congress began to change their mind and involuntarily removal seemed like a good idea. Friends of the Native-Americans came to their defense, especially the missionaries who worked among them. Jeremiah F. Evarts and Samuel Austin Worcester were two of the most vocal.

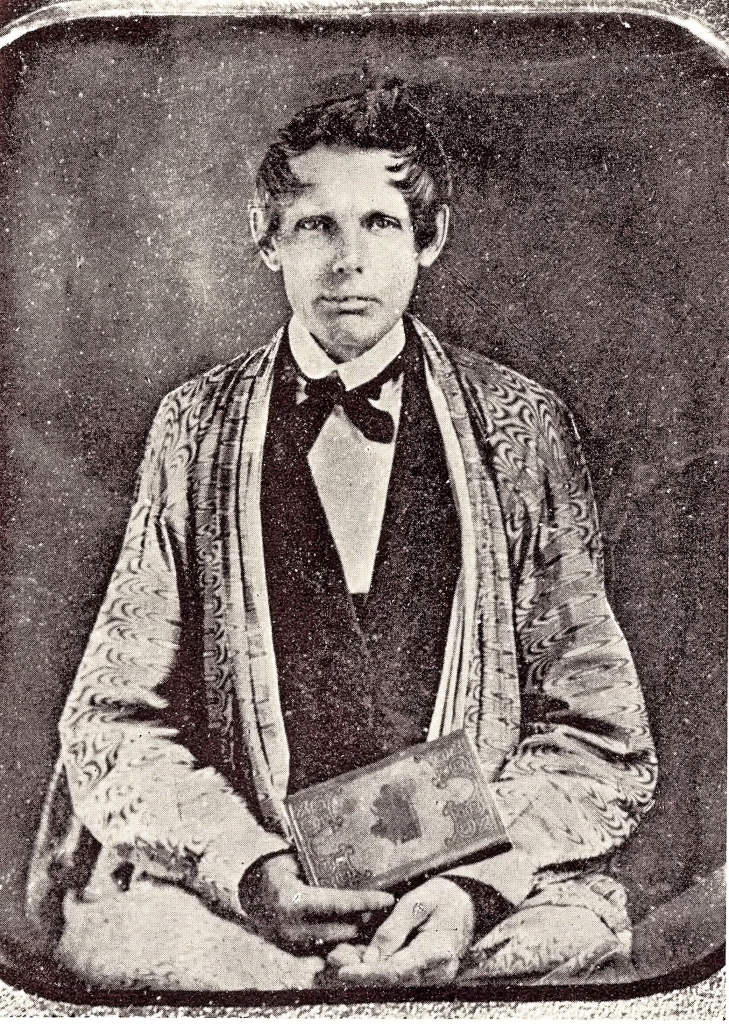

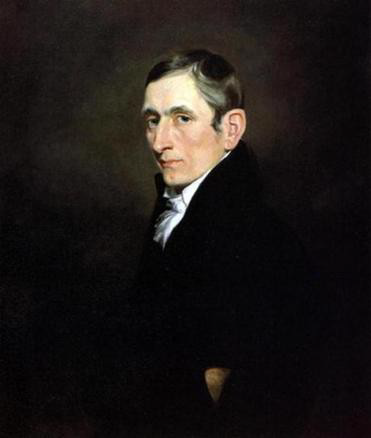

Samuel Austin Worcester

Samuel Austin Worcester, born January 19, 1798, in Vermont, was a missionary to the Cherokee at Brainerd Mission in Georgia, and a translator of the Bible.

Join our Alabama Pioneers Patron Community!

See how to Become an Alabama Pioneers Patron

He collaborated with Elias Boudinot, the nephew of Major Ridge, a wealthy and politically prominent Cherokee National Council member, to establish the first Cherokee newspaper. Boudinot and Worcester had become close friends over the two years they had known each other. After the Cherokee, Sequoyah, developed a syllabary to create a writing system for the Cherokee language, Boudinot asked Worcester to use his printing experience to establish a Cherokee newspaper. The two men helped produce the Cherokee Phoenix, which first rolled off the press on February 21, 1828, at New Echota (now Calhoun, Georgia).

Worcester was arrested and convicted for disobeying Georgia’s law restricting white missionaries from living in Cherokee territory without a state license. The governor defied the summons that the missionary be released, and he was kept in prison for over a year. He died in 1859 in the Cherokee Nation.

Jeremiah F. Evarts

Jeremiah F. Evarts (February 3, 1781 – May 10, 1831) pen name was William Penn. He was a Christian missionary, reformer, and activist for the rights of Native-Americans. He was a graduate of Yale College in 1802 and a lawyer. His wife, Mehitable Sherman, was a daughter of the Roger Sherman, a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence.

At the close of the year 1817, the health of Jeremiah Evarts became seriously impaired, and he was advised by his physician, that relaxation from business and a visit to a milder climate were of essential importance to its restoration so he set out for Savannah, Georgia on the 20th of January, 1818 after taking care of matters related to his business.

On this visit to the south, Evarts spent some time at a mission school for the Cherokees and in 1819, he became concerned about the “critical state of the Cherokees and other Indian tribes.” as talk of removal of the Indians began to develop in governmental circles.1

Evarts began to write against their removal and lobbied extensively against the Indian Removal Act Excerpts from some of his writings around 18292 are worthy of note. In an essay, he states the following regarding the plan to remove the Indians west to the Arkansas territory:

It is a suspicious circumstance, that the wishes and supposed interests of the whites, and not the benefit of the Indians, afford all the impulse, under which Georgia and her advocates appear to act. The Indians are in the way of the whites; they must be removed for the gratification of the whites; and this is at the bottom of the plan.

What sort of a community is to be formed here? Indians of different tribes, speaking different languages, in different states of civilization, are to be crowded together under one government. . . Indians of different tribes, speaking different languages, and all in a state of vexation and discouragement, would live on bad terms with each other, and quarrels would be inevitable.

The most impartial accounts of the country, to the west of Missouri and Arkansas, united in representing it as a boundless prairie, with narrow strips of forest trees, on the margin of rivers. The good land, including all that could be brought into use by partially civilized men, is stated to be comparatively small. Government cannot fulfil its promises to emigrating Indians.

Let not the government trifle with the word guaranty. If the Indians are removed, let it be said, in an open and manly tone, that they are removed because we have the power to remove them, and there is a political reason for doing it; and that they will be removed again, whenever the whites demand their removal, in a style sufficiently clamorous and imperious to make trouble for the government. . . If existing treaties are not observed, the Indians can have no confidence in the United States.

Nothing of this kind has ever yet been done, certainly not on a large scale, by Anglo-Americans. To us, as a nation, it will be a new thing under the sun. We have never yet acted upon the principle of seizing the lands of peaceable Indians, and compelling them to remove. We have never yet declared treaties with them to be mere waste paper.

In defense of the Cherokees, Evarts described them in 1829 with the following:

“that they have always been called brothers and children by the President of the United States, and by all other public functionaries speaking in the name of the country;—that they have been encouraged and aided in rising to a state of civilization, by our national government and benevolent associations of individuals;—that one great motive presented to their minds by the government, has uniformly been the hope and expectation of a permanent residence, as farmers and mechanics, upon the lands of their ancestors, and the enjoyment of wise laws, administered by themselves, upon truly republican principles;—that, relying upon these guaranties, and sustained by such a hope, and aided in the cultivation of their minds and hearts by benevolent individuals stationed among them at their own request, and partly at the charge of the general government, they have greatly risen in their character, condition, and prospects;—that they have a regularly organized government of their own, consisting of legislative, judicial, and executive departments, formed by the advice of the third President of the United States, and now in easy and natural operation;—that a majority of the people can read their own language, which was never reduced to writing till less than seven years ago, and never printed till within less than two years;—that a considerable number of the young and some of the older can read and write the English language;—that ten or twelve schools are now attended by Cherokee children;—that, for years past, unassisted native Cherokees have been able to transact public business, by written communications, which, to say the least, need not fear a comparison, in point of style, sense, and argument, with many communications made to them by some of the highest functionaries of our national government;—that these Cherokees, in their treatment of whites, as in their intercourse with each other, are mild in their manners, and hospitable in their feelings and conduct;—and, to crown the whole, that they are bound to us by the ties of Christianity which they profess, and which many of them exemplify as members of regular Christian churches.

These are the men whose country is to be wrested from them, and who are to be brought under the laws of Georgia without their own consent. These civilized and educated men;—these orderly members of a society, raised, in part, by the fostering care of our national government, from rude materials, but now exhibiting a good degree of symmetry and beauty;—these laborious farmers and practical republicans;—these dependent allies, who committed their all to our good faith, on the ‘guaranty’ of Gen. Washington, the ‘assurance’ of Mr. Jefferson, and the re-assurance of Gen. Jackson and Mr. Calhoun, sanctioned, as these several acts were, by the Senate of the United States;—these citizens of the Cherokee nation,’ as we called them in the treaty of Holston;—these fellow Christians, regular members of Moravian, Presbyterian, Baptist, and Methodist churches, fellow-citizens with the saints and of the household of God, are to be suddenly brought under the laws of Georgia, according to which they can be neither witnesses nor parties in a court of justice. Under the laws, did I say? It is a monstrous perversion to call such a state of things, living under law. They are to be made outlaws on the land of their fathers; and, in this condition, to be allowed the privilege of choosing between exile and chains.

When the Indian Act of Removal was passed by Congress on March 4, 1830, Jeremiah wrote this in his journal, “Did not learn the disposition of the Indian bill in the Senate till this morning; am greatly disturbed and mortified, for our country’s sake, that the vote stands worse than I had thought in any degree probable.”3

Jeremiah Evarts. staunchly wrote against the Indian Removal Act until he died of tuberculosis on May 10, 1831. Many believe he had overworked himself in the campaign against the Indian Removal Act. He is buried in Connecticut.

1Essays on the Present Crisis in the Condition of the American Indians By Jeremiah Evarts, Perkins and Marvin, 1829

2Essays on the Present Crisis in the Condition of the American Indians By Jeremiah Evarts, Perkins and Marvin, 1829

3Memoir of the Life of Jeremiah Evarts, by Ebenezer Carter Tracy, Crocker and Brewster, 1845

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Removal– some additional stories

- Plan for Indian Removal Started With President Thomas Jefferson

- Intrigue and Murder After Treaty At Indian Springs

- President Adams And Governor In A Stand-off

- Gold Causes Expulsion Of The Cherokees

- Cherokee Chief Ross Became Homeless