In the story Native Americans fought on both sides of the Civil War , only the five Native American tribes were mentioned. The Catawba Indians have often been left out of historical accounts. A reader graciously shared this information about the Catawbas and their participation in the Civil War. The The Catawba Nation is the only federally recognized tribe in the state of South Carolina.

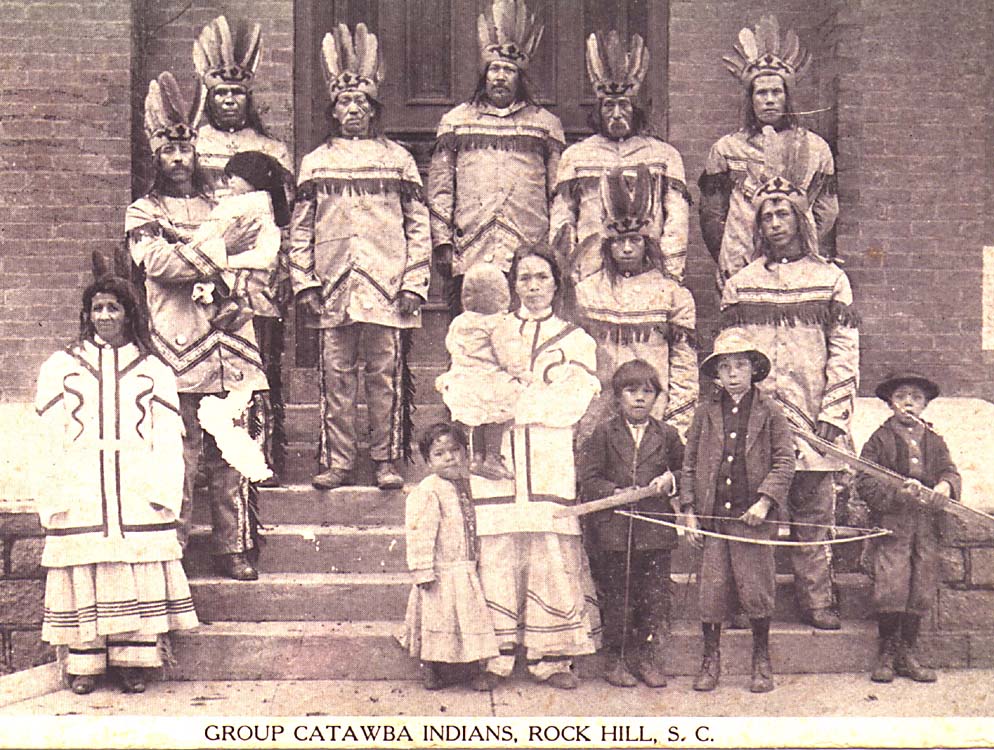

Photograph below from Wikipedia

“The Catawba Indians, though a war-like nation, were ever friends of the white settlers. They aided and fought with the Americans in the Revolution, and the Confederates during the Civil War. Tradition says they immigrated to this portion of South Carolina from Canada about 1600, numbering some12,000. Their wars with the Cherokee, Shawnee and other nations, together with the smallpox, depleted their numbers greatly. In 1764 the province of South Carolina alloted them 15 miles square in York and Lancaster counties. About 1840 a new treaty was made, the State buying all their land, and afterwards laid them off 800 acres on the west bank of the Eswa Tavora (Catawba River), six miles south of Fort Mill, where the remnant, about 75, now live, receiving a small annuity From the State.

Taken from, the Rear Die of the Monument in Columbia, South Carolina, Dedicated to Catawba Indians

Some Noted Catawba’s

King Hagler,

Gen. New River,

Gen. Jim Kegg,

Col. David Harris,

Major John Joe,

Capt. Billie George,

Lieut. Phillips Kegg,

Sallie New River,

Pollie Ayers,

Peter Harris

This is on the East Base of the Monument.

The West Base of the Monument Bears the following: Some of the Soldiers in the Confederate Army:

Jeff Ayers,

John Brown

William Cantey

Bob Crawford

Billy George

Gilbert George

Nelson George

Bob (Robert) Head

Epp Harris

Jim Harris

John Harris

Peter Harris

Robert Marsh (Mush?)

Bill Sanders

John Sanders

John Scott

Alex Timins (Tims?)

The Following Inscription is on the Front Die of the Monument

1600

Erected

To The

Catawba Indians

By

Sam’l Elliot White

And

James McKee Spratt

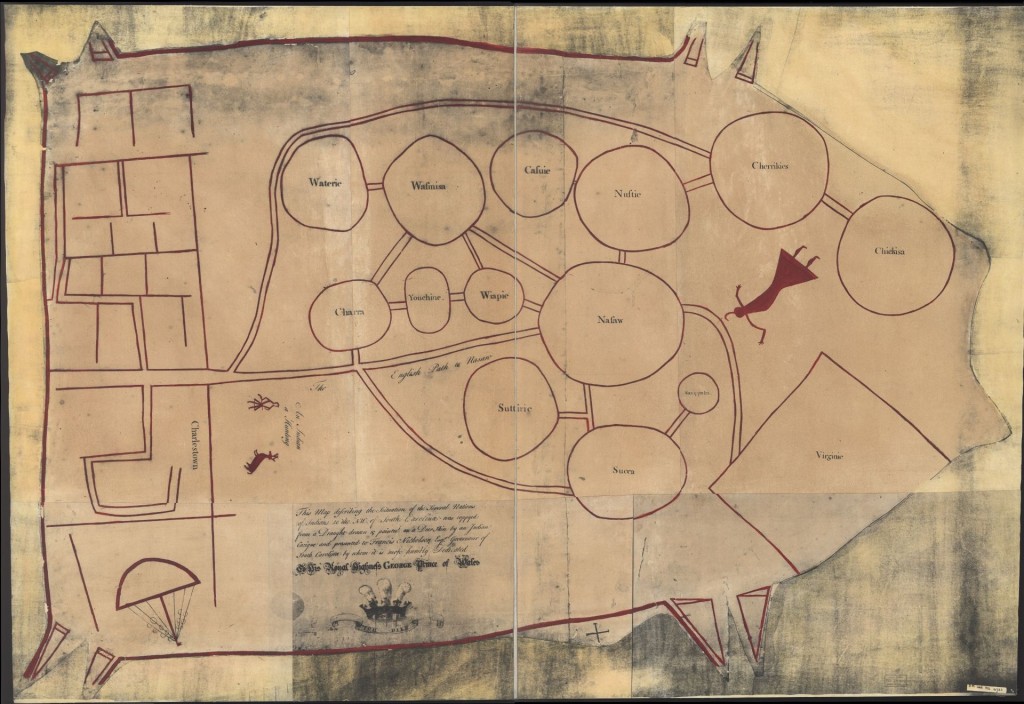

The Catawba Map below is from Wikipedia Map made by a Catawba chief in 1721 and given to South Carolina colonial Governor Francis Nicholson. The circles represent different tribes, and Charleston is to the left.

American Indians – 20,000 of whom fought in the War Between the States – played their most Prominent role in the Civil war’s Eastern Theater during the Petersburg Campaign From July 1864 – March 1865, especially in the June 30 Battle of the Crater. Iroquois from western New York State, Pequot’s from southern New England, and Catawba of South Carolina fought in that battle. Most of them served in the Union Army of the Potomac’s “White” regiments, Although they were sometimes segregated into all Indian Companies within those units. A substantial minority fought in U.S. Colored Troops (U.S.C.T) units Alongside Black soldiers and a sparkling of other people of color. Others sided with Confederate defenders, Joining Integrated, even elite units.

Catawba’s served in the 5th, 12th, and 17 South Carolina Infantry. They fought in some of the war’s bloodiest battles – Antietam, Gettysburg, and Petersburg – most of them serving in Capt. Cadwalder Jones’s Co. H of the 12th South Carolina. The Catawba of the 17th South Carolina went into the Petersburg trenches With Brigadier General Stephen Elliot, Jr’s Brigade in may 1864 and would remain there until Apr. 1865, helping to defend against six Union assaults on the city.

While we may never know the full story of Catawba participation in the War Between the States, surviving records in the South Carolina Department of Archives and History suggest the great suffering and profound personal tragedies experienced by the patriotic Catawba. For instance, Agent John R. Patton’s report of November 1864 is quite graphic in its description:

… To the Honorable the Senate and House of Representatives

Now met and sitting on General Assemble I, J.R. Patton agent for

The Catawba Indians, would most Respectfully Beg Leave to

Present my 4th Annual Report. The tribe numbers at this

Time between eighty and one hundred. All if the males Accept

3 are now or have been on the service of the Confederate States Five

of whom have died in the service, one or two discharged from

Physical Disability. Two of three have been Severely Wounded

and one of them a cripple for life. There has been a great deal of

Sicknesses in the Nation during the present year and several have

died. I am at present unable to Report any change in the condition

of the tribe for the better. The remain the same careless

indolent peoples they have always been letting every day as it

were provide for itself; as a matter of course, many of them are

at times considerably straitened to get food enough to satisfy the

natural cravings of hunger. There is at present 3 in number (who)

belong to the soldier board of relief who draw supplies

whether in kind or money through my hands which being dealt

out to them as these necessities Requires it has prevented that class

from suffering. There is but very few who have made anything in

the way of provisions….

Service Records

One may discard previous attempts to compile an accurate Catawba Indian Confederate Roll and enumerate a more accurate list taken from surviving military records found in the national archives, though even this roll must be read with caution. Not all the Confederates records survived the chaos that followed the surrender at Appomattox. Other files are clearly incomplete. The roll gleaned from surviving archival records contains the names of eleven Catawba veterans. Catawba tradition adds an additional five individuals whose records apparently have been lost. These tell us much of the Catawba war experience.

The first Catawba enlisted in Company K, South Carolina Seventeenth Infantry, on Dec. 9, 1861. This Group included four men. A brief description of each follows:

Jefferson Ayers – war the husband of Emily Cobb. At the time of his enlistment, he was the father of Jefferson (Buddy) Ayers and Alice Ayers. He was wounded at the battle of Boonsboro on Sept. 14, 1862 and was sent home to recover. He returned to service on Oct 3, 1862, and fought in the battles of Kingston (Dec. 14,1862), Goldsboro (Dec. 17, 1862), Sumter James Island (Nov 1863), and Petersburg (Summer 1864). He was wounded again on March 25, 1865, at the battle of Hatcher Run. He was captured on May 6, 1865, and war sent to point lookout, Maryland, where he died as a prisoner of war on July 2, 1865.

William Cantey – Fought in the second battle of Manassas (August 30, 1862), and at Boonsboro (September 14, 1862) and Sharpsburg (September 17, 1862). He took ill at camp in Culpepper and was hospitalized at Richmond. He returned to duty in November 1862 and fought in the battles of Kingston and Goldsboro (December 1862). He was discharged on February 3, 1863, at the end of his first enlistment.

John Scott – Fought in the battles of Kingston and Goldsboro (December 1862) and was discharged on February 3, 1863. He served as chief of the Catawba for several terms during the balance of the war and into the 1880’s

Alexander Tims (Timins?)– Was wounded at the second battle of Manassas (August 30, 1862). He returned to duty on January 1863 and fought at the trenches in front of Petersburg and in the battle of Petersburg (July and August 1863). He remained in the trenches at Petersburg until February 1865. In 1880 he attended his company’s reunion. Three years later he emigrated to Sanford, Colorado, where his descendants are members of the Colorado Catawba Band.

The second group of Catawba Joined Company H, Twelfth South Carolina Infantry, on December 20, 1861. It consisted of two brothers:

James Harris – was the husband of Sarah Jane Harris and the father of James, Martha, and David A. Harris. He was wounded at Antietam on September 17, 1862. He returned to service in July 1862 and fought at Gettysburg (July 1, 1863) and Liberty Mills (October 1863) and helped demolish the Orange and Alexander Railroad (October 1863). From May to August 1864, he fought at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Jericho Ford, Fraziers Farm, Fossel’s Mills, and Reams Station. James Harris was among those who surrendered at Appomattox. The monument that marks his grave in the Old Reservation Cemetery reads: “Jim Harris, Died May 1874, aged 30 years. He was a brave Soldier of the 12th Reg.”

John Harris – who had visited the Choctaw Nation in 1860 as part of the Catawba delegation, took part in the battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862. While engaged in the fight there he was shot through one of his legs and when it appeared that he might fall into the hands of the enemy he begged his comrades to kill him rather than permit this to happen. He was sent to a hospital in Frederick, Maryland, and took part in the exchanged of prisoners in 1863. In 1864 he was in the Invalid Corp. John Harris was chief to the Catawba from 1869 to 1871.

On May 13, 1862, the third Catawba contingent, including three men, enlisted in Company G, Fifth South Carolina Infantry:

Robert Crawford – was the husband of Margaret Jane Crawford and the father of Betsy Crawford. He was last seen on December 31, 1862, in the vicinity of Fredericksburg, Virginia, and was assumed killed in action.

Epp Harris –

Robert Head – was reported as a patient at the Episcopal Church Hospital, Williamsburg, Virginia, on September 12, 1863, and later appeared on a register of soldiers who died of wounds and disease. The Head family later emigrated to Sanford, Colorado, where descendants still reside.

Peter Harris – was the Husband of Elizabeth Harris and the father of David, Edward, and Butler Harris. Between November 1862 and June 1863 he was treated at hospitals in Williamsburg and Farmville, Virginia, for a wound he received at Sharpsburg. He was taken prisoner on April 2, 1865, at Petersburg and remained a prisoner or war at Hart’s Island in New York Harbor until the end of the war. Some years after the war, the Fort Mills Times published a short account of Harris’s service:

At the Battle of Sharpsburg he was severely wounded through

the knee and fell to the ground unable to walk. Realizing the

danger from the enemy’s fire to which his position subjected him,

Peter crawled backward 50 yards to a place of safety, supporting

his injured leg by resting it upon the other one. After the wound

healed, Peter returned to his company and continued to the end of

the war to fight for the Confederacy.

The enlistment for 1863 consists of one man:

Robert Mush (Marsh?) – enlisted in Company K, Seventeenth South Carolina Infantry, on April 4, 1863, at Wilmington, North Carolina. On June 4, 1864, he was a patient at Episcopal Church Hospital, Williamsburg, Virginia, suffering from chronic diarrhea. He was sent home on a furlough and died there on August 28, 1864.

The last group enlistment in Company H, Twelfth South Carolina Infantry, occurred on March 11, 1864. It included two men, William Cantey (Second enlistment) and Nelson George:

William Cantey – also joined Company H at Orange Court House, Virginia. From May to August 1684, he fought at Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Jericho Ford, and Petersburg. His last record is dated July 7, 1864, According to Catawba tradition, he died in war.

Nelson George – also joined Company H at Orange Court House, Virginia. From May to August 1684, he fought at Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Riddles Shops, Jericho Ford, and Petersburg. He was reported missing on August 25, 1864, and was probably taken prisoner of war at the battle of Reams Station. He was paroled as a prisoner of war on May 16, 1865, at Charlotte, North Carolina.

The five individuals listed below are claimed to be Confederate veterans by Catawba tradition though no National Archives records have been located for them:

Franklyn Cantey – was probably William Cantey’s brother. According to Catawba tradition, he was killed in the war. His name appears on an 1849 Catawba census for the Greenville District as aged twenty-three, so he would have been Thirty-Five at the outbreak of the War Between the States.

John Brown – was the Husband of Margaret Brown and the father of John Brown and Sallie Gordon. According to Catawba tradition he died as a result of the war in 1867 shortly after his son John was born.

Gilbert George (Billy?) – is held to be a Catawba Confederate veteran by Catawba tradition. He appears as an adult male in agents’ report as late as 1869.

John Sanders – served in the Confederate army and died in the war, according to Catawba tradition. He may be linked to Lucinda Harris who had a son John Sanders. A John Sanders, who may have been married to a Nancy Sanders, appears in an 1859 agent’s report.

William Sanders – also died in the war, according to Catawba tradition. William Sanders may have been too young to appear in the 1859 agent’s report along with John and Nancy Sanders, but most likely was a member of their family.

According to Catawba Tradition and beliefs they worshiped a Deity known as “He-Who-Never-Dies”. They also believed that the soul of a person who had been killed demanded retribution in order to rest in peace. If a member of the tribe were killed, men would go out to avenge the death, and if successful, bring back a scalp as evidence of revenge. Catawba men wore loin cloths made of deerskin. During wartime, they painted a black circle around one eye and a white circle around the other. Catawba women wore Knee length Skirts of Deerskin. During winter and when traveling, men and women wore pants, leggings, and capes made of various animal hides. Men and women wore jewelry made of shells, beads, and copper… and on special occasions they painted their skin.

Over 60,000 Englishmen and Canadians served the Union as well as a varied selection of Frenchmen, Scandinavians, Hungarians, and even a very few Orientals. The 79th Ny was made up of mostly Scotsmen who wore Kilts early on the war, until derisive laughter of fellow soldier every time they climbed over a fence drove them to adopt trousers.

Often overlooked in both armies were much smaller numbers of Native Minorities who wore Blue and Grey. Perhaps as many as 12,000 Indians served the Confederacy, Most of them members of the Five Civilized Tribes Living out in the Indian Territory. In all, the Confederacy would raise some eleven regiments and seven Battalions of Indian Cavalry out there, not to mention a few hundred red men scattered through some of the White confederate regiments from North Carolina, Tennessee and Kentucky. They did not exactly look the picture of the Rebel Soldier. “Their faces were painted, and their long straight hair, tied in a queue, hung down behind”. Wrote a Missouri Confederate. “Their dress was chiefly in the Indian costume – Buckskin hunting shirt, and moccasins of the same material, with little bells, rattles, ear rings, and similar paraphernalia. Many of them were bareheaded and about half carried only bows and arrows, tomahawks, and war clubs.”

Ill-treated and ignored even by their own superiors, the Indian soldiers had only half a heart in the cause, and much the same could be said of the 6,000 or more who wore the Blue. All too often they were enlisted only to take advantage of old tribal hatred, pitting Union Indians against Confederate Indians and all too often they ignored Army Regulations and fought in the old ways. But they certainly lent color to the muster rolls of the North and South. Spring Fox, Big Mush Dirt Eater, Alex Scarce Water, John Bearmeat, and Jumper Duck, were all soldiers of the Union and these were simply Anglicization’s of Indian names Probably impossible to pronounce.

Approximately 20,000 Native Americans served in the Union and Confederate armies during the Civil War, participating in such battles as Pea Ridge, Second Manassas, Antietam, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, and in Federal assaults on Petersburg. By fighting with the white man, Native Americans hoped to gain favor with the prevailing government by supporting the war effort. They also saw war service as a means to end discrimination and relocation from ancestral lands to western territories. Instead, the Civil War proved to be the Native American’s last effort to stop the tidal wave of American expansion. While the war raged and African Americans were proclaimed free, the U.S government continued its policies of pacification and removal of Native Americans.

In the East, many tribes that had yet to suffer removal took sides in the Civil War. The Thomas Legion, an Eastern Band of Confederate Cherokee, led by Col. William Holland Thomas, fought in the mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina. Another 200 formed the Junaluska Zouaves. Nearly all Catawba adult males served in the south in the 5th 12th and 17th South Carolina Volunteer Infantry, Army of Northern Virginia. They distinguished themselves in the Peninsula Campaign, at Second Manassas, and Antietam, and in the trenches at Petersburg. As a consequece of the regiments’ high rate of dead and wounded, the continued existence of the Catawba people was jeopardized.

In Virginia and North Carolina, the Pamunkey and Lumbee chose to serve the Union. The Pamunkey served as civilian and naval pilots for Union warships and transports, while the Lumbee acted as guerillas. Members of the Iroquois Nation joined Co. K, 5th Pa Volunteer Infantry while the Powhatan served as land guides, river pilots, and spies for the Army of the Potomac. During the Civil War there was no distinctions made when a Native American joined the U.S Colored Troops. Well into the Twentieth century, the word “colored” included not only African Americans, but Native Americans as well. Individual accounts reveal that many Pequot from New England served in the 31st U.S. Colored Infantry of the Army of the Potomac, as well as other U.S.C.T. regiments.

The most famous Native American unit in the Union Army in the east was Company K of the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters. The bulk of this unit was Ottawa, Delaware, Huron Oneida, Potawami and Ojibwa. They were assigned to the Army of the Potomac just as Gen Ulysses S. Grant assumed command. Company K participated in the battle of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, and captured 600 Confederate troops at Shand House east of Petersburg. In their final military engagement at the Battle of the Crater, Petersburg, Virginia, on July 30, 1864, the Sharpshooters found themselves surrounded with little ammunition. A lieutenant of the 13 U.S C.T. described their actions as “Splendid work. Some of them were mortally wounded, and drawing their blouses over their faces, they chanted a death song and died – four of them in a group.”

At least 15 regiments and battalions were enlisted from the Cherokee, Choctaw, Osage, Creek, Chickasaw, and Seminoles of the South.” Many “often enlisted for private reasons of their own which had nothing to do with the Confederate cause”. There were a significant number of them enlisted in the service. It is estimated that as many as 12,000 Indians served the Confederacy, of whom most were members of the Five Civilized Tribes living out in the Indian Territory (now present-day Oklahoma). Also, they came from many more tribes scattered throughout the Confederacy, serving in North Carolina and also in segregated units with whites in North and South Carolina, Tennessee and Kentucky. Why did Native-Americans enlist to fight for the Confederacy?

In the Indian Territory, the Five Civilized Tribes of the Southeast (their origin before removal in the 1830s by the U.S. government)-the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, Seminole, and Cherokee-were in a dilemma at the outbreak of the Civil War. They were torn between the North and South. Neutrality was difficult to keep, and sides were to be taken. “They were dependent peoples as a result of American wars of conquest, treaties, or economic, political, social, and religious changes introduced by the ‘Long Knives'”. The Choctaw and Chickasaw sided with the Confederate government. There surely was distrust between these two tribes and Washington, and that was probably a good enough speculation for them joining the South. The three remaining tribes had more complex reasons.

The Seminole, Creek, and Cherokee all had similar reasons for choosing sides. All three had splits that consisted of two parties, which were treaty and non-treaty factions. The reference to treaties refers to the ones signed (or refused to be signed) by the various tribes with the U.S. government for removal to what was to become the Indian Territory. The Creek division seemed to date back even farther because “the split among the Creeks was an ancient one. At the time of removal from Georgia, it almost flared into open warfare”.

The Southern side in every divided tribe was always the treaty faction. The largest (and considered the most significant) of the Five Tribes was the Cherokee. Stand Watie led the Southern (and slave-holding faction) of the Cherokee. John Ross led the Northern faction that consisted of mostly abolitionists (ironically, Ross was a major owner with about 100 slaves), and he was also the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. Most of Watie’s relatives were assassinated by Ross’s followers after the relocation treaty, and Stand Watie himself survived numerous attempts on his life. He was the last remaining member of the four Cherokees who signed the treaty. To survive “he organized his own military force at Beattie’s Prairie and Old Fort Wayne in Indian Territory which protected him and his followers”. Many of these men followed Watie into the Confederate service.

What is not well known (besides the fact that the Cherokee were slave owners), was that both parties signed the Treaty for Allegiance with the Confederacy, but only one had the intention of honoring it. How appropriate that the Union fraction emulated what the Washington government had been doing for years to them, and that was to sign a treaty with no intention of following its terms! Watie’s followers viewed Ross’s faction in the same way they viewed the U.S. government, which was through dislike and suspicion and this incident increased those feelings. The Confederacy did a better job than the Union in honoring its promises to the Native-Americans. “As a symbol of the Confederate commitment to the Indians, the treaty also provided that the Cherokee were to be allowed a delegate in the Confederate Congress at Richmond”.

The Eastern Band of the Cherokee were located at Quallatown, North Carolina. They had remained by co-operating with the state and national governments. Their main reason for enlisting was to follow a white man who was adopted by the Cherokee at a young age and had worked constantly with the North Carolina state government to give concessions to let the Cherokees stay in Quallatown indefinitely. The man was William Holland Thomas, and to the Cherokee he was Wil-Usdi. The Cherokees’ belief in him was indeed strong, but there were other than sentimental reasons for this attachment. They had “an anomalous legal and political status, claiming to be Citizen Indians, yet not have their person or lands protected under state and federal laws.” Also, “their desperate economic condition and their inability to purchase land for themselves because of racial restrictions made them overtly dependent on Wil-Usdi, their patron saint and benefactor”.

The Eastern Band of Cherokees main motivation for enlisting to fight for the Confederacy and North Carolina, being to stay in Quallatown, was actually honored by the state. “On February 19, 1866, the North Carolina General Assembly granted a specific affirmation of the Cherokees’ right to residency in the state”.Sadly, Thomas’ luck declined rapidly after the war, and he died at the age of 88, on May 10, 1893, in an insane asylum.

The Catawba Indians of South Carolina loyally served the Confederacy. They were a small tribe of only 55 people at the outbreak of war and only 19 of them were fit for service. One reason for their enlisting was that “to prove oneself in war was the highest manly virtue and a requirement for political leadership”. It could be stated, “for the Catawba, as well for many white southerners, combat was a proving ground for manliness.” The Confederate $50 enlistment bounty was another significant motivation. Being relied upon by the planters to be slave catchers also had something to do with enlisting.

As can been seen, the Native- Americans enlisted for many reasons, from the distrust of the Federal government, to distrust between themselves. They were dependent on whites for survival, but would fight for and against them to assert the time honored right of any proud people, that being pride in who they are. Individual Indians may have had many differing motivations for enlisting in the Civil War, but they all shared that sense of pride.

If Native-Americans would enlist to fight for the South, what about African -Americans, an idea which is difficult for the twentieth century public, which was raised on the over- simplified reason that slavery alone was the main reason the War Between the States was fought, to comprehend. It is indeed a controversial subject to deal with. What prompted African- Americans to enlist to fight for the South? “It is often forgotten that while slavery was the major underlying cause of the Civil War, its abolition was not the original objective of the U.S. Government”. The slaves had nothing to gain from a Union victory at that time for their status would have remained the same. The North was a racist as the South in many respects, due to the fact that many Northerners had never seen an African-American. Faced with these “hostile invaders”, many free blacks “volunteered to defend their homes against the new threat from the North.” Sadly, “no accurate record has been kept of black units that served the South, since most of them were state militia and never mustered into the Confederate Army”. Many free blacks and slaves were accepted into the Confederate Army as laborers, teamsters, and cooks.

———

Addendum by Judy Canty Martin

Fascinating…..

Fascinating…..

I would suggest that those who throw around words like,genocide,have a chat with what’s left if the Catawba Indians

Awesome story thanks for the post. I salute my fellow veterans and this is another prime example of our country not taking care of its veterans 🙁

The war of 1812 too.

You tell the story as if the Catawbas wanted to fight for the white man as an honor. No I tell you the real reason was the threats of whites to kill them and their families if they did not join. I have a different documented account of how the whites got my ancestor Robert Marsh to go fight . The whites were already starving them and robbing the rents they were supposed to be paying to the Catawbas. Some of the families left the reservation to find work in other areas so they could have food. Over time they were removed from the tribal rolls as in my Marsh line. Thanks old man Boss Hanna

Even the ones who made it home after the war were ill treated by the whites and were not acknowledged for what they had done for many years.

Boss Hanna, I understand that the Whites mistreated, not just the Catawba but all of the Native Americans. It wasn’t my intention to show that they weren’t, it was to show that they were involved in the civil war and not forgotten as a tribe.

Glad they fought on the right side!

Note facial hair !

Its possible 3rd GGF James Mush was possibly Catawba

Thank You Montez for sharing.

Fascinating history of the Catawbas! Few people realize the last Confederate general to surrender was Stand Watie, a Cherokee.

As noted in Shelby Foote’s 3 volume “Civil War”.

Interesting.

Pete Clark

Fascinating!

I wonder if the Marsh is a relative.

There was lots of arrow heads and Indian mounds at our old place in Lawley Ala. We collected lots of arrows out of garden spot. The Indian mounds were in woods near home. Hicks place.

I love this fb page…always interesting:)!

My father resembles these men and so do my uncles.

A lot of Sanders 🙂 my grand daddy

This was so interesting

And there are more than listed in the article….

David Anson Ayers, Co. H, 17th N.C. Infantry, and Co. K, 3rd N.C. Cavalry

Asa Ayers, Co. F, 10th Florida Infantry

Ben Ayers, Co. F, 10th Florida Infantry

Will Ayers, Co. F, 10th Florida Infantry

Thomas Ayers, Co. H, 5th Florida Infantry

The foregoing men descend from Col. Ayers aka Hixa-Uraw who was chief at the Treaty of Augusta 1763, and Capt. Ayers, both of whom were war chiefs of the Catawba during the French Indian War.

Robert Head – is my 5th great grand father. I do know some of the Head family resides in, CO, UT, NM, and AZ.. Mostly in NM

My great grandfather was asst principal Cherokee chief that would lead one of trail of tears through Alabama an married Susannah hosford red eagle sister granddaughter an had 9 children with ..an there children married Indians from Mcghee clan maniac clan an Rolin. Clan an on an signed one treaty with Andrew Jackson keep land died in Pensacola Florida at suspected age 101 fell off his Poarch broke his neck drunk his monument is in Oklahoma

I’m the great x3 granddaughter of Susannah and Richard Taylor via William H Taylor and thenMinnie Lee Taylor. I’d love to know more about Richard and Susannah’s history

The Pee Dee Band is proud to announce its legal incorporation in the state of Georgia February 16, 2016. This is a great moment in our history, because we as American Pee Dee Indians, are the first North American Tribe, indigenous to the state of “Carolina”, to be allowed to organize and hold legal birth records, as American Indians. The significance of this is that some of our bloodlines can be traced back to slavery, putting an end to the plantation slave system of race determination by Jim Crow methods. The last remnants of slavery have been officially dismantled, when the state of North Carolina issued birth records for the Pee Dee Band bloodlines, using scientific measurement, two parent heritage (dating back to before 1820), and issuing state identification, rather than using Jim Crow methods of race determination.

Pee Dee Indians have legally organized in the state of South Carolina, who also have some common distant relatives to the Pee Dee Band, LLC. These Indians are officially recognized by the state of SC. The North Carolina Pee Dee Band’s heritage dates back to the civilization of river Indians in the state of Carolina. This era is before the great migration of the Cherokee Nation on the “Trail of Tears”, to their new homeland, in the western section of North Carolina. It is believed by the Pee Dee Band, that that trail included some areas of camp sites along the Pee Dee River in Anson County, based on some of the Cherokee facial characteristics markings of our people. How we differ from the Cherokees is that, 1) some of our people merged with descendents of slaves and slave owners, 3) some merged with Cherokee transients, 4) some of our people merged with members of other North Carolina river Indians, 4) we have a portion of our population who carry and have recessive trait eye color (blue, green, and hazel); North Carolina includes recessive trait eye color of Indians, in their state’s history. The state has run a play on the very issue, for the last 100 years.

We are proud to have legally banded and it is our intent to procure our legal rights as an indigenous people, refusing to pass along our rights to be known as American Indians, and refusing to pass those rights and civil liberties to foreign immigrants, who will benefit from our heritage.

We fought on the side of the colonists.

At that point we already been on our tribal lands for over 4000 years.

My Tribe was decimated with the smallpox 1732 – 1739. We went from 1600 families to 60. I have a scanned copy of the original letter from George Washington to My Tribe in 1776.

Asking them to side with the colonists and that they would honor our land and are land treaties…… we fought as Scouts/ Catawba Rovers for the Americans.

in 1756 my grandfather negotiated 15 Acres in Salisbury North Carolina through Thomas Dobbs for the King of England.

King George granted My Tribe 15 Acres in present-day Rock Hill South Carolina.

All my grandfathers were Catawba Indians.

Chief New River and Arataswa ( King Hagler)

And General Jacob Scott.

My family of Catawba heritage is through my maternal grandmother (Kimbal/Harris lines). Your information seems to be correct with some of the books I have purchased to research the Catawba Nation from early colonial periods to the 21 century. What about Red Tick also known as Touchesay who was the fearless one in the French and Indian War as well as the American Revolutionary War. He was one King Hagler’s top rated warriors (the best). His likeness was painted in an oil portrait and hangs in the University of South Carolina’s Library, Columbia, South Carolina. Glad to know you. Elizabeth grand daughter of Ida Mae Kimbal (Harris and Kimbal lineage)

Just wanted to remind you that the United States is a “war-like” nation, and is not friends with a lot of people.

Did you forget to burn your flag of the Confederacy?

WHITE FOLKS GOT THEM ON FOOD STAMPS

Sorry but this photo reminds me of those cigar store indians statues I used to see in western movies.

interesting!

[…] Source: The Catawba Indians, though a war-like nation, were friends of the white settlers | Alabama Pioneers […]

For those interested, look up the “Catawba Braves” of Company K, 46th NC Regiment (NCV, Infantry). They fought alongside River Indians such as Co. A “Lumberton Guards”; Co. E “Tar River Rebels”; Co. I “Coharie Guards. The Tar River Rebels of Granville County are thought to have PeeDee Indian ancestors w/in their ranks (study of PeeDee surnames present on Co. E pay & muster rolls.

Interesting!

Never knew that,very interesting

I have letters from my GG grandmother from North West Alabama during the civil War she writes about how all the men where off to war and Indian raiders and Native American Confederate Soilders would come and raid their smoke house at night…

Rusty Crane read the post I made a week ago…doublehead (mom’s side of the family) evidently he didn’t get along with anyone

Thank you for sharing so much Alabama history. We enjoyed living there while filming historical records and loved your state. It’s beautiful and the people so friendly.

From my genealogical research, my Dad’s grandmother was a Catawba.